Adelina Shaidullina: You’ve told the story of your studio dozens of times already. To me it sounded like “Jakob wanted to create a studio, and Nils wanted to create a studio, and we never worked together before starting a business.” Didn’t you think that was too risky?

Nils Thomsen: It was almost 10 years ago. I knew Jakob because he was also studying at my university in Kiel, and we were both starting out in type design. Getting exposure or clients was challenging for an independent designer producing one or two typefaces per year. It was also hard to find colleagues with similar skills and goals.

I felt that Jakob and I shared the same vision, so I simply asked if he was interested in starting a foundry, and he said, “Yes, I’m thinking about it.” Since we didn’t know each other well, we didn’t risk our friendship being affected by business.

We didn’t know where the journey would

AS: Would you recommend this approach to a person who wants to start a studio these days?

NT: It’s always better to start something than just plan to start something.

Conto Collection designed by Nils Thomsen in 2014

Jakob Runge: The funny thing is, when Lisa joined after three years of TypeMates, we had to calculate the company’s value to determine her entry fee. At that moment, we realized that, in the first two years, we hadn’t earned anything specific for running the foundry. Our income came from creating typefaces and selling licenses, but there was no business plan. Looking back, I think it was good not to focus on one. If we had a business plan and saw no perspective for our business after two years, we might have shut everything down. Instead, we kept going, until, fortunately, the business started to work out.

Ilya Ruderman: I imagine it was super cheap for Lisa to join you guys after three years then!

JR: Actually, no, because the third year went really well.

IR: So there are three partners now?

JR: Yes, and it’s funny because, on our website, we call Nils and me founding partners, while

IR: Smart move.

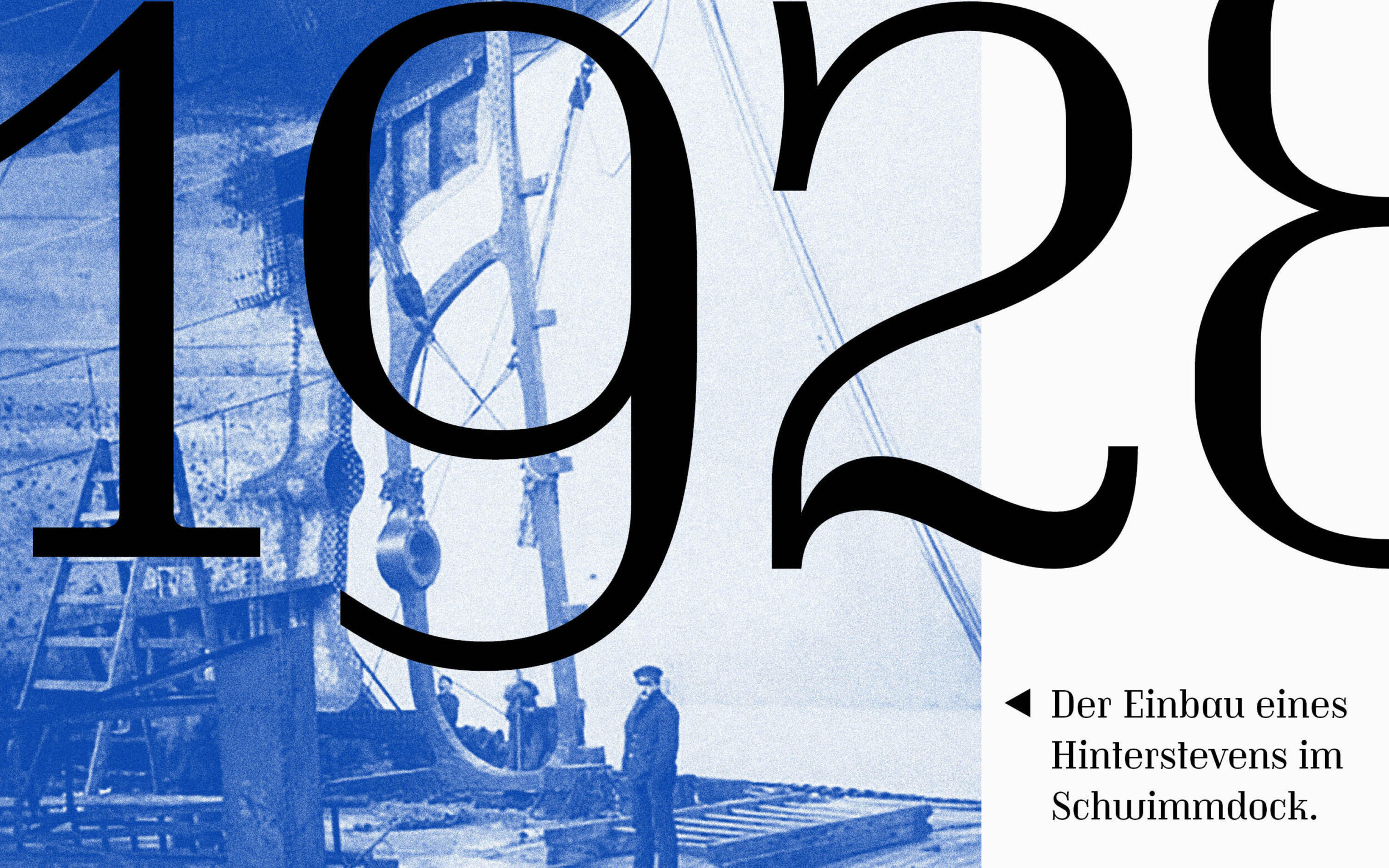

Harrison Serif designed by Jakob Runge and Lisa Fischbach in 2018

AS: Ilya, would you consider bringing on a managing partner?

IR: Unfortunately, it would be extremely expensive for anyone to join us. Our platform is complex, and it’s not profitable enough to justify such a big financial risk. I wouldn’t recommend anyone to join us.

JR: Thinking about someone joining us now, we’re also facing a challenge for our custom projects and revenue model. With three partners, any new idea requires convincing both Nils and Lisa. If there were four or five people, I think it would be even harder to keep things moving.

IR: The bigger the board, the slower you move.

NT: Is it better to have one king!

JR: I think TypeMates benefits from being a collective. It was not Nils’ foundry or Jakob’s

AS: This discussion is getting dangerous since the one-king idea came up… let’s switch topics. Albert-Jan Pool was your teacher, and now you publish his typefaces. How does that feel?

NT: It’s different because we didn’t meet in person for the collaboration. Back in school, we saw each other every week and chatted, but that was 15 years ago. Now, our discussions happen over email, and it feels different, but it’s an honour that he chose to publish with us. It’s his way of saying, “My students have done a good job and have a great foundry. I can release my new typeface with them.”

Altona designed by Antonia Cornelius, Albert-Jan Pool and Julia Uplegger in 2024

Alison Head and Alison Text designed by Antonia Cornelius, Albert-Jan Pool and Julia Uplegger in 2024

JR: Most of our external designers just accept our encodings, workflow, and production methods. Albert had a lot of different ideas and opinions. For instance, he argued about whether to use tabular currency symbols. Albert is strongly against them. It was an enriching challenge for us. We’ll feel very proud to have worked with him. Many of our designers, like Philip Neumeyer, also studied Albert’s way of doing stuff.

What I really admire about Albert is that he respects your design approach. He won’t tell a student what’s best but will ask questions instead, acting more like a coach than a king. People who studied with him have learned to be flexible and open to ideas, rather than rigidly following one way of doing things.

Norbert designed by Philip Neumeyer in 2021

IR: I met Albert-Jan Pool for the first time 20 years ago. I was in TypeMedia, and he visited The Hague. At the time, he was mainly known as the author of DIN. He brought some archive materials, which was impressive. Back then, he seemed quite open-minded, though he could be stubborn about certain visions, especially concerning revivals where you need to respect the original.

I can imagine, though, that it might be hard to convince him about certain things or standards. Designers of his generation, who often sold fonts through platforms like Linotype, might be a bit distanced from the real clients. Sometimes, they get caught up in theoretical ideas about clients’ needs, whereas we’re in direct contact with our clients. Sometimes we do need to deliver tabular currency symbols, and that’s totally fine. We can debate their aesthetic, but clients need them.

Royal Prussian Railway Administration master drawings (1897) which influenced the design of FF DIN

FF DIN designed by Albert-Jan Pool in 1995

JR: Actually, I like tabular figures. Sometimes, I use them as default figures. If the Euro sign works in the tabular version, I’ll just make everything tabular.

IR: That won’t work for all the currencies. Remember Peseta, the old currency? It’s represented by three letters, Pts. It’s tough to fit into a tabular version.

JR: True, but our current encoding doesn’t even include the shekel symbol by default, so it’s easier to create a tabular figures set.

A 1970s typewriter with the Pts symbol

AS: You attend legibility conferences and work with researchers, but aren’t most legibility tips just common sense?

JR: I had this conversation with Antonia, the author of Cera Mono. She’s done a lot of legibility research, and from her perspective, it’s often about finding scientific proof for what we already know intuitively. When you’ve worked with type for years, you understand things like spacing, letter differentiation, and rhythm. But for those outside the type design world, having scientific evidence really helps. Simply saying “I know from experience” doesn’t usually convince people to switch from Helvetica to a more legible typeface.

Cera Mono designed by Antonia Cornelius in 2024

AS: When someone applies to publish their font with you, how do you decide whether to accept it or not?

NT: We start by looking at our library to see if the typeface fits with what we already have. We ask if it complements our collection, or if it’s too similar to existing fonts, or if it’s a style we don’t plan to pursue. Sometimes we see something that doesn’t fit our typical style but would add variety, which can be a great addition to TypeMates. Another factor is whether the designer will finish the project, especially if we don’t know them personally. That’s hard to guess from emails alone. We’ve worked with some designers where the communication was easy and their fonts went live quickly. But in one case, after many discussions, the designer went silent for two years, and their typeface is just sitting in our ideas folder. It would have been a great addition to our library.

JR: One reason is that most designers who submit typefaces to us aren’t full-time type designers. They do graphic design and create typefaces on the side, so it takes them a long time to finish a typeface. For us, it’s

We once discussed whether our library should have a consistent profile. For example, Commercial Type has a profile, so people who like one font from them often also like others. But since the three of us have different styles, our library naturally has a huge variety of styles. In a way, we can accept almost any style from other designers because we have a more chameleon-like library.

NT: Right now, we’re also considering if a typeface will sell well. We’ve had some releases that we knew wouldn’t be big sellers but went forward anyway, putting in a lot of effort, even if it didn’t pay off. Still, it’s

Dockland designed by Tom Holloway (who is a full-time UX designer) in 2023

IR: I have a question about planning. Some time ago, I was talking to Dino dos Santos, who runs DSType Foundry. He shared nearly five years’ worth of planned releases with me. He had carefully mapped out when he would work on each project. How far ahead do you plan?

NT: One or two

JR: Another reason is that, as we also do custom work and administration, it can take us two or three years to finish a typeface. We plan ahead because we know we won’t finish sooner.

Miura Slab designed by Dino dos Santos and Pedro Leal and released by DSType Foundry in 2024

Miura Slab designed by Dino dos Santos and Pedro Leal and released by DSType Foundry in 2024

Agna designed by Pedro Leal and released by DSType Foundry in 2024

Agna designed by Pedro Leal and released by DSType Foundry in 2024

IR: It’s similar for us. I’d love to plan that far in advance, but in my experience, urgent custom projects always come up, pushing deadlines back. How do you manage to meet your deadlines?

NT: Well, we have three partners.

JR: We might look bigger than we are. Since there are three of us, if each of us completes a typeface every three years, we’re still able to release at least one typeface per year. So, it seems like we’re super productive, but individually we’re not, because we’re occupied with other work that pays the bills.

IR: We have only two, so we just need a third!

AS: Nils, this question is for you. From what I understand, you co-founded a foundry, you run a bikepacking club, and you’re also involved in a Dj-label. How do you find the time and motivation to design retail typefaces?

NT: Starting a foundry was really driven by my passion for designing retail typefaces. That was the original

So, designing retail typefaces has always been my passion. But when I joined forces with Jakob, it turned into more

I use my communication design skills to contribute to my other projects. If you’re passionate about something, it doesn’t feel like work. For me, the desire to create has always been the core.

Hackenpedder bikepacking club logo designed byI Nils Thomsen

Hackenpedder bikepacking club logo designed byI Nils Thomsen

Hackenpedder bikepacking club merch designed byI Nils Thomsen

Hackenpedder bikepacking club merch designed byI Nils Thomsen

AS: Jakob, a personal question for you as well. Answering our questionnaire, you mentioned that a good type designer is someone who can control their ego. Isn’t it difficult to promote your typeface while repressing your ego?

JR: For me, it’s almost like a mantra to step back from my ego in order to create something useful. It’s about designing not just what I like, but what others might find useful. But to be honest, most of the time I design things I like and then see if others find them useful too. So, it’s more of an idea than what actually happens in practice.

In reality, we probably market our egos more than we’d like to admit. Going back

NT: I think it’s an approach that Jakob and I, and Lisa, share. People often say, “Wow, you’ve done such great work for such big clients, yet you seem like regular people!” We don’t hide the work we’ve done for high-end clients, but we just don’t overpromote TypeMates either.

JR: Right, most of us have this down-to-earth approach. But on the other hand, if we work with a big client and put together a case study, we’ll highlight that it’s a major player in Europe or in their field. It’s not that we’re

AS: Speaking of big clients, you’ve designed typefaces for Rossmann and even FC Bayern Munich. Cera is on Lego boxes and in the Witcher. Do you feel responsible for shaping how an average

JR: I’m not sure if people actually notice those typefaces. Most people who see legal documents or products probably don’t think about the typeface. Also, with Rossmann, when you tell someone who isn’t in graphic design that you did the typeface for their local drugstore, they might say, “Wow, that’s cool!” Or when I mention that we created a typeface for FC Bayern Munich, people get excited. The typeface might not be funky, but the client is huge. And when I tell someone who is a woodworker, that we worked with Bayern Munich, they start to understand that you can make a living from type design. A lot of people don’t believe that even graphic design can be a full-time profession. Even designers sometimes think that creating typefaces is just a hobby, not something you can actually live off of.

FC Bayern Sans designed by TypeMates in 2017

NT: You are right that we do have some contemporary typefaces out in the world. However, many of our clients tend to want their branding rather less expressive. They look for solid, reliable typefaces, and Rossmann is a great example of that. What we often hear from people who aren’t deeply into typography is that they only remember the display font on the start and pay buttons or in the app. We designed about 20 sans-serif fonts, yet it’s always the one poster style that stands out.

JR: I think at one point, we even came up with the slogan «No hype, just type» for ourselves. It fits because, if we compare our typefaces to those created by Dinamo, I sometimes feel a bit envious of how they can create this contemporary vibe that everyone loves. Whatever sans they make, it has a special flair. But we’ve accepted that we’re not those

Type system for Rossmann designed by TypeMates in 2023

IR: When we look at the world from an independent industry perspective, we see a lot of fonts made by our friends and our own, but still, the typography around us is much richer. There are so many layers of historical typography on the streets and all around us. I dream of a time when all the typography we see comes from independent typographers, but for now, the majority is still made up of Arial, Times New Roman, San Francisco, and other big names. We’re a tiny, tiny market, unfortunately. Even with big clients, there’s still so much that could be more unique than it is right now.

AS: It’s a bit of a random question, but typefaces in your collection almost always come with great icon sets. Why do you enjoy designing them so much?

NT: I’m not sure, but after spending a lot of time designing a typeface, you eventually reach a point where it’s just post-production. There’s nothing left to design because the creative part is really just a small phase of the project. Creating an icon, though, is a nice, quick task that doesn’t require much work or time, but it still adds something to the typeface in the end. It’s a refreshing creative moment. And sometimes, like with Comspot, we did it for

Icons in Comspot designed by Nils Thomsen in 2017

JR: Speaking of marketing, we have a typeface called Rumiko, by Natalie

Natalie

Icons in Rumiko designed by Natalie Rauch in 2022

Icons in Netto designed by Daniel Utz in 2023

AS: What do you think about the relationship between AI and type design?

JR: Honestly, type design hasn’t become as intertwined with AI as I thought it would. With its pattern-based system, type design seems like it would lend itself easily to AI learning or machine learning. But for now, it’s a small market, so there isn’t a big budget to train models to recognize various typefaces. I remember about six years ago, David from Rosetta Type gave a presentation on machine learning, and it was

NT: I think most typefaces from independent designers live on personality and the unique ideas in each letter. An AI could be helpful for quickly generating

Examples of font style interpolation with the help of AI. From the Font Style Interpolation with Diffusion Models research paper, 2024

Examples of font style interpolation with the help of AI. From the Font Style Interpolation with Diffusion Models research paper, 2024

JR: I consider AI as an assistant in the early stages. I’ve heard similar things from people about logo design. So clients generate whatever they want and get a rough idea of what it looks like. And then they come to a designer saying, “Okay, this

IR: I have other concerns about our profession, ones not related to AI. Observing the industry, I see a lot of young designers joining and a lot of new studios emerging. We’re seeing many new releases, sometimes secondary clones of existing typefaces. But sometimes, there are new designers with fresh ideas, which is exciting. The competition is increasing, and I am afraid we might reach a point where there may not be enough clients, and demand for new releases might drop.

JR: I have mixed feelings about that too. As a designer, you might hesitate to buy another font because you already have so many. We see this with our own releases,

NT: For us, I think, quite a lot has changed in 2013. That was when Jakob was finishing Franziska, and a year before, I completed the Meret typeface. I remember getting a lot of feedback online at the time. But if you release something today, it feels like no one really notices. Maybe a few people buy it or share the link, but there’s rarely a comment. With five or six typefaces releasing daily, who has the time to comment on or choose which one is worth talking about?

I think the amount of content is making it hard to focus. This shift might be changing our role as type designers. Clients now need help navigating the market; they can’t look at MyFonts and easily decide which font they need since there are 50 similar options. So, we’re doing more client support, and that’s maybe what’s really changing our job.

For an independent designer with just one typeface, the key to getting noticed might be strategic marketing, to not get forgotten after the release. But for us, we’re an established foundry with 50 fonts, so we continue, monitor the market, and adapt as needed. Consulting has become a big part of our work, and that’s just the reality we’re embracing.

Meret designed by Nils Thomsen in 2010

Franziska designed by Jakob Runge in 2014 and updated in 2024

JR: Even if there are many versions of the same design or genre, the licensing approach can differ widely across foundries. Some clients come to us specifically because of our licensing model, which isn’t even that unique, but it’s straightforward. They say, «The licensing is good; what typefaces do you have?» They’ll often pick between just two slab serif options because we don’t have an overwhelming selection in that genre, but they’re happy because the licensing suits them.

So my view is optimistic. In the past, the challenge was the design itself; now it’s navigating licensing. And in the future, there will be a new challenge, but there’s always a way to stand

Edie & Eddy Slab designed by Lisa Fischbach in 2022

Muriza designed by Jürgen Schwarz and Jakob Runge in 2015

AS: Instead of a one-time purchase, some foundries now have a subscription model where users pay the type designer monthly. What do you think of that?

NT: We considered it but decided not to go with the subscription model. Of course, it’s cheaper for designers to have a tool they only pay for once, but we live from a lot of people buying it one time.

Fontstand has a good concept of a subscription model,

JR: Today, Monotype is pushing the market toward the subscription model, and many clients come to us because we don’t use it. In the long run, we’re more affordable. But if people get used to the Monotype model in five years, maybe we’ll reconsider our model then. It’s hard to say right now.

AS: What other business could you, Jakob and Nils, build together if not a type studio?

NT: A hiking club in Bavaria!

JR: I have no idea. I know some people go into business just to be in business, regardless of what it is, but I can’t see myself doing anything outside of type design.

AS: So you don’t like hiking?

JR: I have no idea how you make money out of hiking. I’m just fine with selling typefaces.

IR: You didn’t ask me, but if Yury and I had to start a new business, my first thought

AS: I’m looking forward to it, even though I’ll lose my job then.