The visual noise of media, memes, and viral formats has given rise to a new design scene in Western political discourse. In this ‘superstorm’

Noemi Biasetton is a design researcher who works at the intersection of visual culture, political theory, and media studies. She perceives design rather as a way of organising meanings and power than as a craft or a set of tools. Her approach is essentially critical design theory, which considers not only what is visualised but also why it is visualised, in whose interest, and with what implications.

Superstorm is a research of how digital media and information technology are transforming political communication and visual culture, and how the role of the designer is changing within the context of this transformation. The superstorm here is a situation where the boundaries between entertainment and politics get blurred, and the information space becomes an arena for the battle for attention, interpretation, and power.

Superstorm: Design and Politics in the Age of Information. Images: Graphic Design Books

For me, this book is important in the context of defining agency and the role of the designer. In our field, it is still widely accepted that design could be kept in a neutral

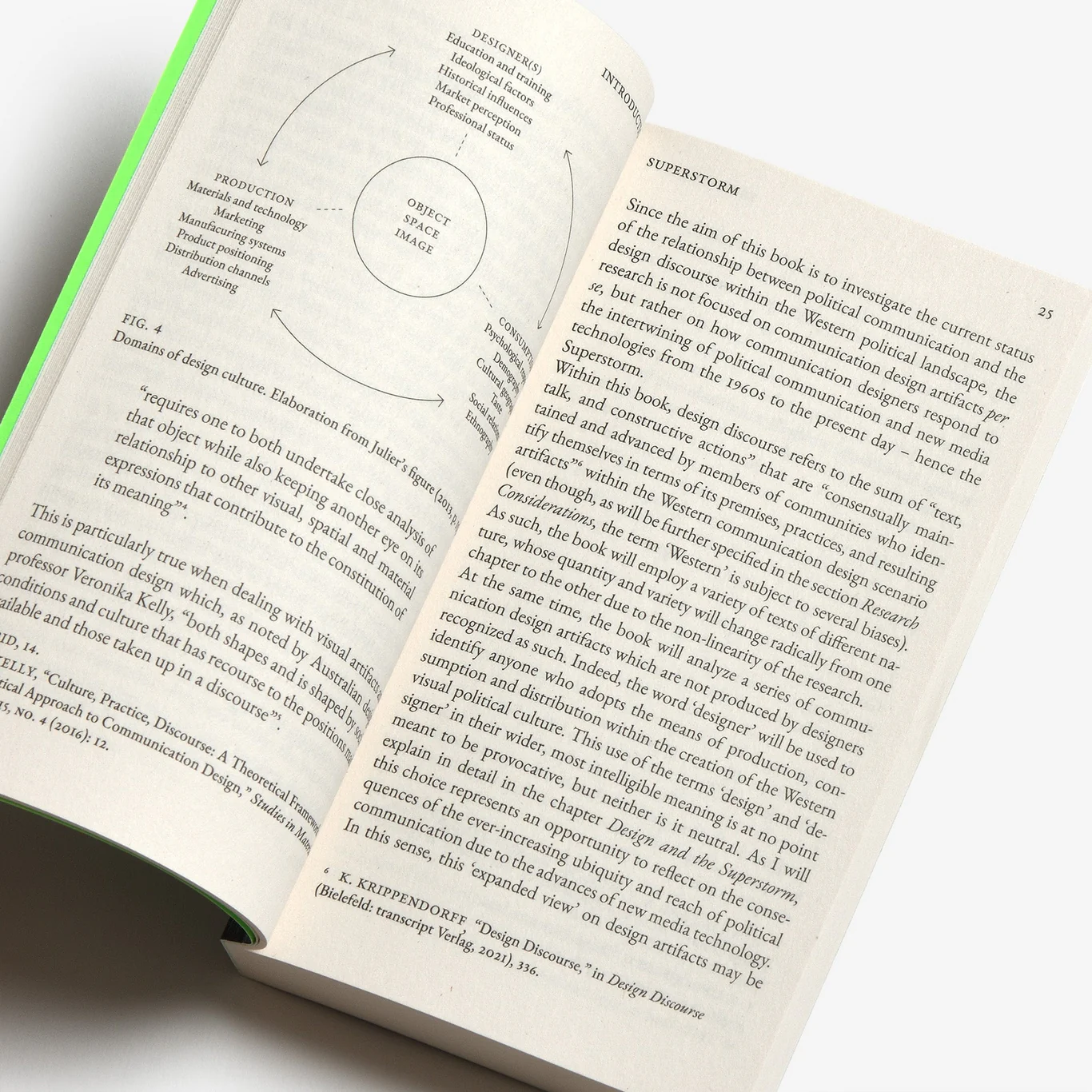

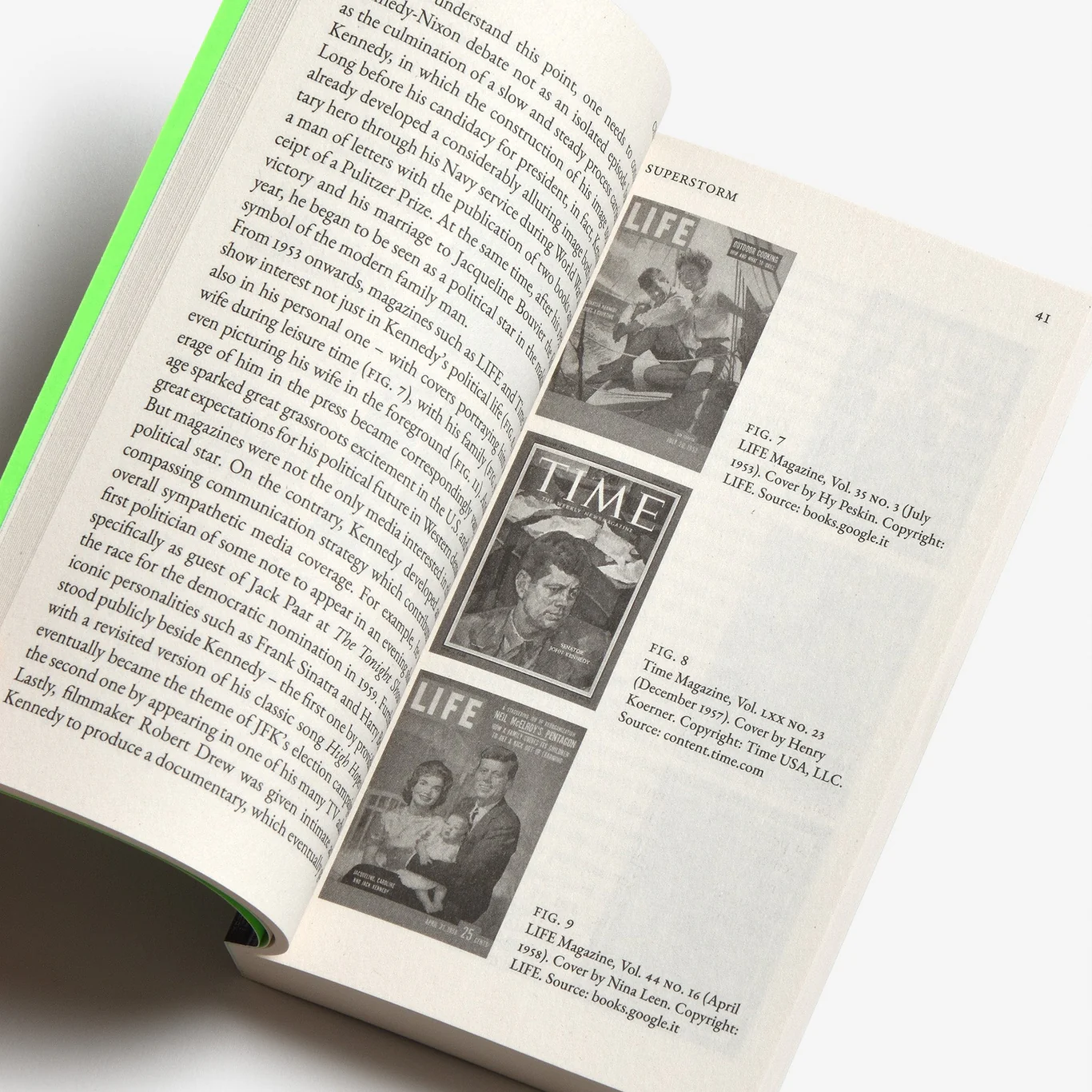

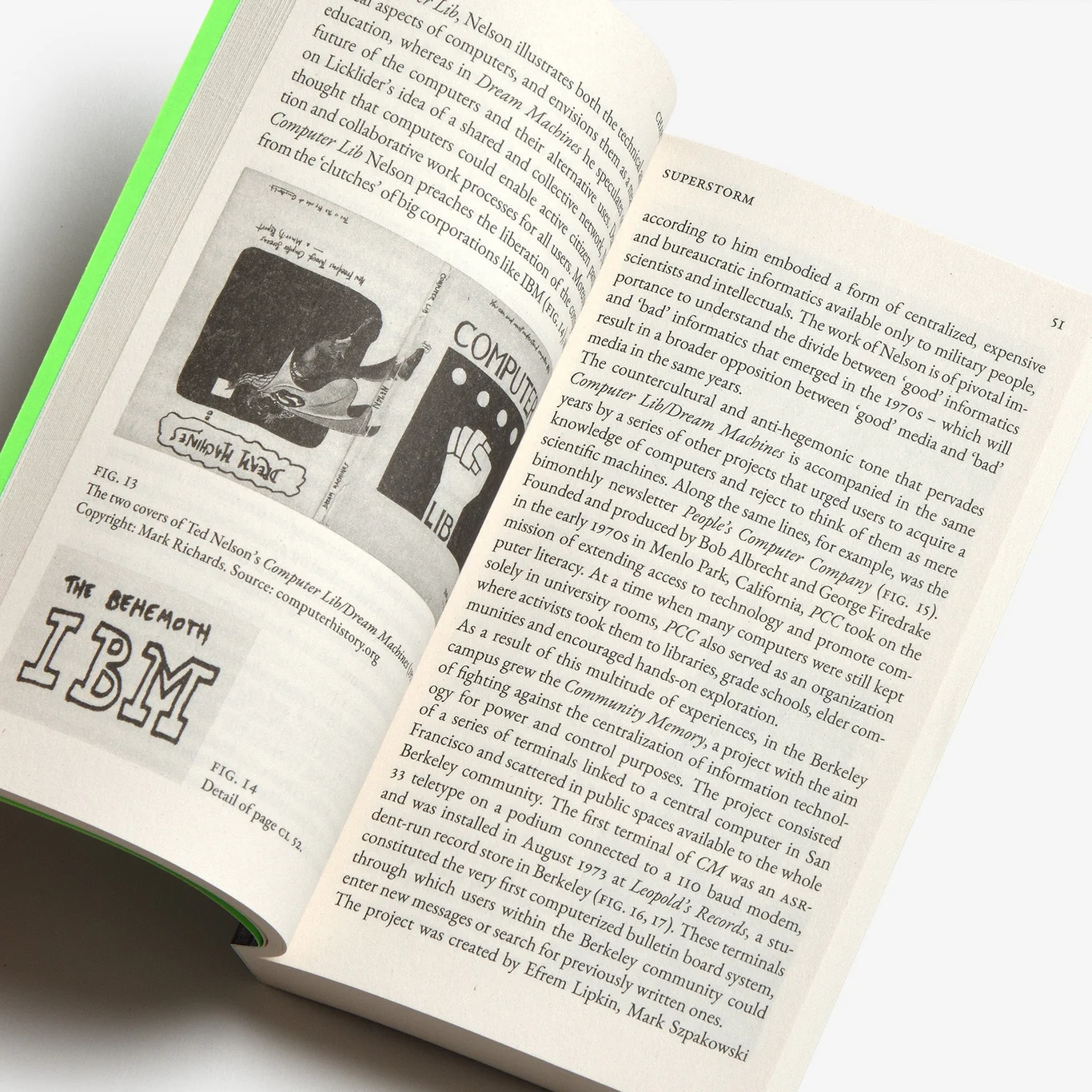

The designer’s agency is revealed in two key aspects: the political nature of the profession and the crisis of authority. Biasetton traces the development of political visual communication since the 1960s, demonstrating how the arrival of new media altered both the structure of political speech and the designer’s place within it. We witness how the redistribution of power, media resources, and communication formats has impacted the designer’s responsibility and their actual role: designers have transitioned from creating aesthetic images intended for passive consumption to developing semantic and cultural strategies. Today, content is no longer a means but an environment where design is shaping (or destroying) political interpretations.

Another key point in the context of defining agency is the issue of authority. One of the important stories here is the story of the Clinton 2016 election campaign, when Michael Bierut was in charge of the campaign’s identity. Despite the ‘appropriateness’ of the visual solution, it was overshadowed by a vibrant populist symbol: a red MAGA cap with a rough font. This episode reveals the limitations of the designer’s power: professional principles proved ineffective in the battle for emotional engagement. ‘While communication professionals ridicule the clumsiness, kitsch and plain bad taste of populist designs, the latter persevere, as they see bad taste, kitsch and clumsiness not as a vice but as a virtue’, writes designer Silvio Lorusso in his introduction to the book.

Clinton 2016 election campaign. Images: Order Design

Make America Great Again cap, 2016. Image: National Museum of American History

Make America Great Again cap, 2016. Image: National Museum of American History

This is not just about the taste, but also about the illusion of control. The title of the book was inspired by a line from Dante Alighieri, ‘A ship without a pilot in great tempest’. Designers tend to think of themselves as pilots, but it’s time to admit that this is un unmanned craft: designers do not control the means of production Biasetton considers media, such as social media or streaming platforms, as means of production, that is, media, and therefore no longer act as middlemen between the customer and the audience. Besides, many have not yet realised that the focus has switched from media to content, so they continue to think and work in outdated paradigms that cannot withstand the Superstorm.

Rather than offering any instructions or guidelines, Biasetton presents designers with a path for self-reflection, a framework through which to develop a conceptual historical-critical approach to their work. She identifies three forms of interaction between design and politics:

-

Design with politics — design on the side of politics: here, the designer caters to an existing political agenda. This could be an identity for an election campaign, a state brand book, or campaign materials. The designer here is rather some kind of technician, participating in delivering a political message or statement, but not generating one.

-

Design about politics: here, the designer becomes an observer and critic. That’s visual projects that analyse, interpret, or document political developments, without directly interfering with them. These could be posters, visual essays, or data visualisation on inequality or polarisation. The designer here is an analyst and commentator.

-

Design of politics: the most radical level. The designer not just designs or analyses politics, but interferes with the political process, creating new forms of publicity, institutions, ways of participation. This could be working on voting interfaces, participatory platforms, alternative

media — that is, design that changes the very structure of interaction between society and the government.

Design with politics. Shepard Fairey’s Hope poster, part of Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign. Image: BBC

Design with politics. Shepard Fairey’s Hope poster, part of Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign. Image: BBC

Design about politics. The Artsakh Crisis by Artem Miltoyan, 2024. A long-read about the victims of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Images: Artem Militonian

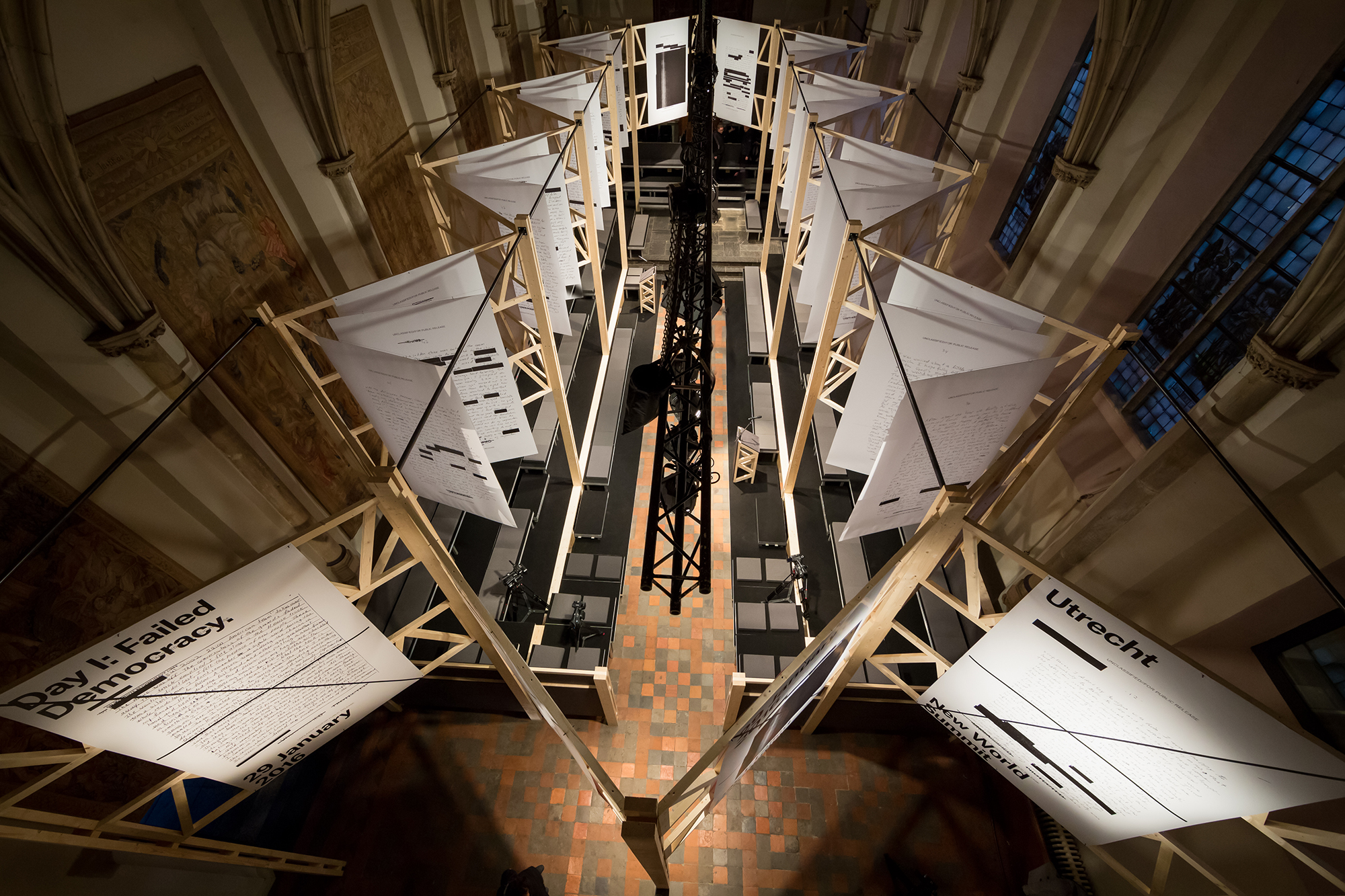

Design of politics. New World Summit by Studio Jonas Staal, 2016. An artistic and political organization that develops parliaments with and for stateless states, autonomist groups, and blacklisted political organizations. Images Jonas Staal

Biasetton believes that it’s precisely this third form, design of politics, that gives the profession its strategic depth. The designer does not create supporting visuals to serve, but designs a scene of political action.

The author brings us to an important conclusion: a critical approach and responsibility are not optional qualities for a designer, but the basis of their agency. Who are we in this system? An instrument of power, an observer, or an active agent? How does the image that we create impact inequality and accessibility? Whose interests does our design

It is a call for mindfulness, for the return of political sensitivity and intellectual responsibility in design. It encourages us to let go of the illusion of control, but not to give up on attempts at meaningful participation.