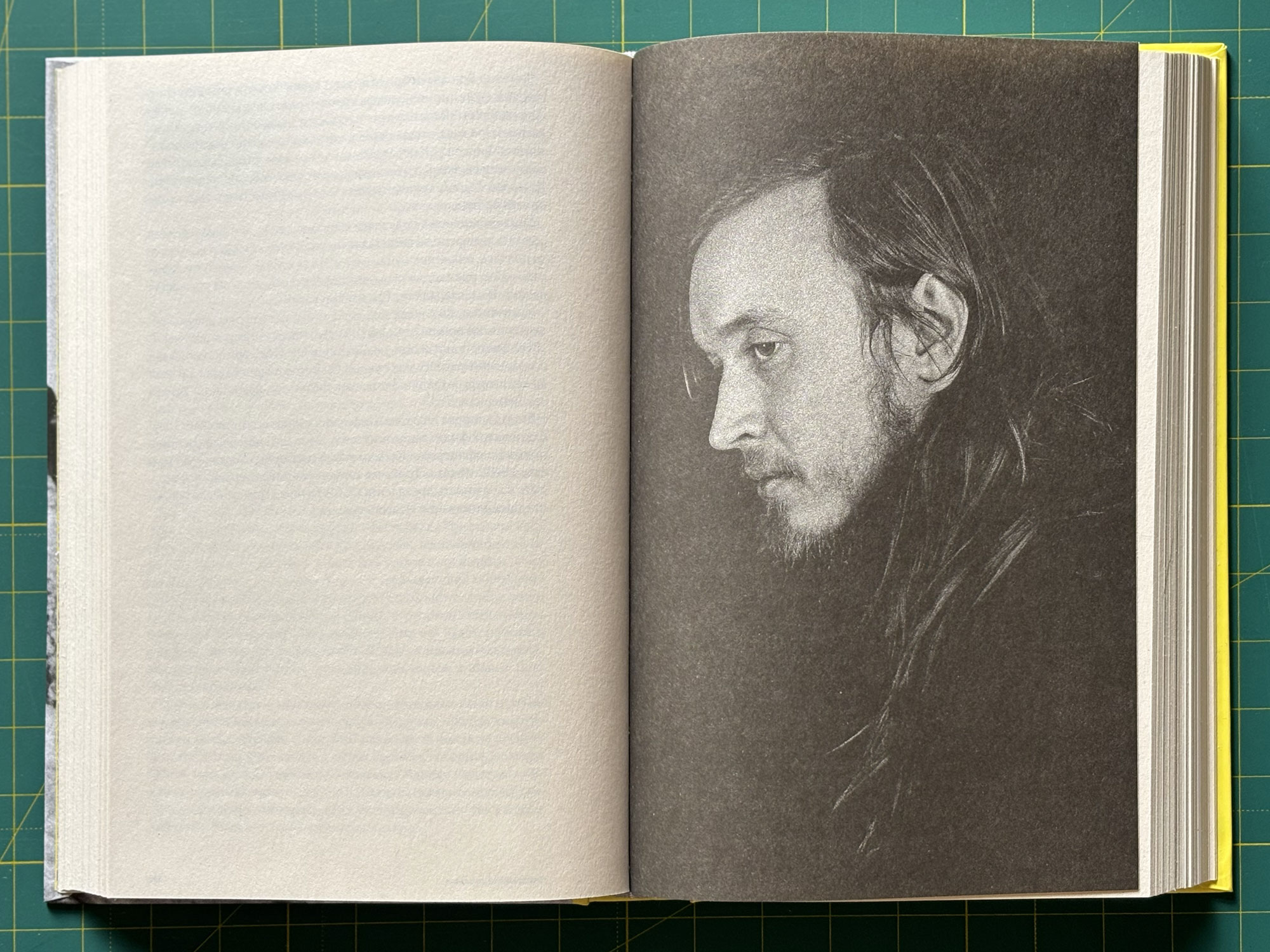

The book He saw the sun. Egor Letov and his time, recently published by Wyrgorod, served as an opportunity to have this conversation. The book was written by Alexander Gorbachev, and designed by Daria Yarzhambek and Yury Ostromentsky. The body text is set in Tekst by East of Rome, Forma DJR by David Jonathan Ross is used for the book’s headings and footnotes, while Loos by CSTM Fonts is applied to the elements that the new Russian legislation requires to be included in books published

In communities of editors and designers working with Russian-language publications, this disclaimer is commonly referred to as ‘е***а’ [yebalá], which roughly translates as ‘crap’, or ‘fucked-up shit’ (The ‘Law on Information, Information Technology,’ and Protection of Information does not allow us to spell out the full word in Russian). Normally, our stories do not contain any obscene language, yet this time we felt that, when talking about censorship practices, preserving this piece of professional slang would be the right thing to do.

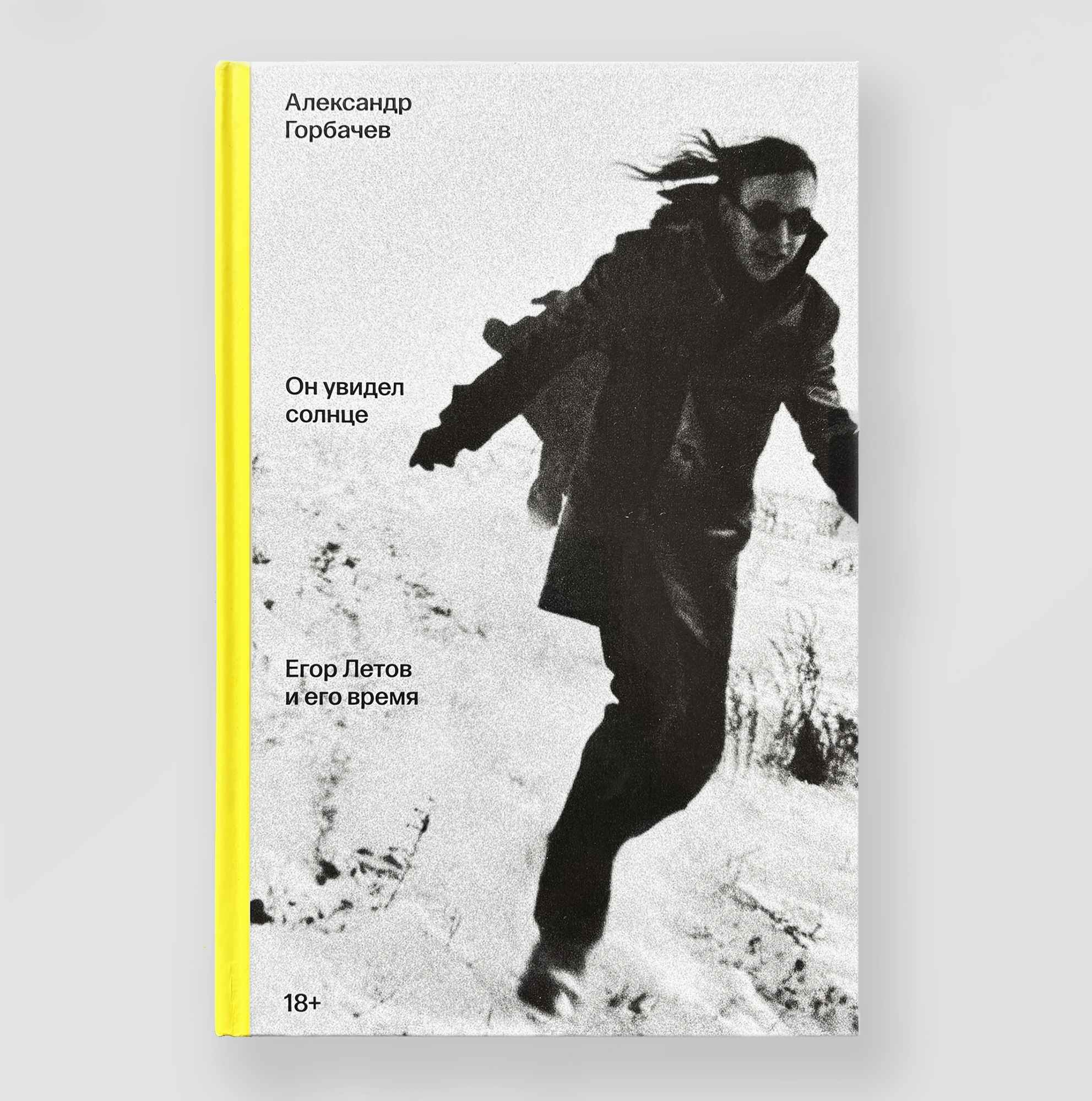

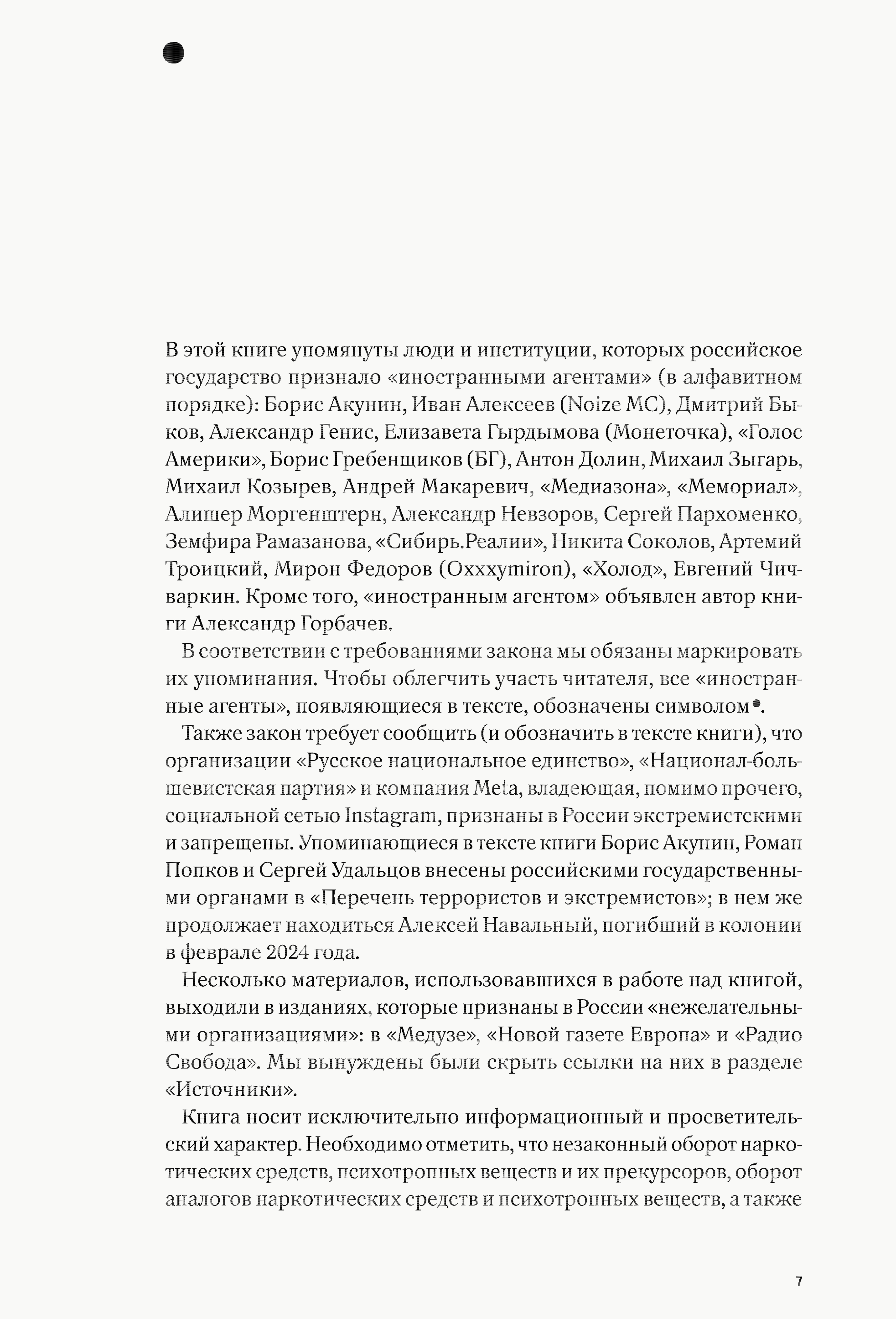

НАСТОЯЩИЙ МАТЕРИАЛ (ИНФОРМАЦИЯ) ПРОИЗВЕДЕН, РАСПРОСТРАНЕН И (ИЛИ) НАПРАВЛЕН ИНОСТРАННЫМ АГЕНТОМ ГОРБАЧЕВЫМ АЛЕКСАНДРОМ ВИТАЛЬЕВИЧЕМ ЛИБО КАСАЕТСЯ ДЕЯТЕЛЬНОСТИ ИНОСТРАННОГО АГЕНТА ГОРБАЧЕВА АЛЕКСАНДРА ВИТАЛЬЕВИЧА

This piece of text is the yebala mentioned above. We have to include it because of the Russian foreign agent law. It requires any person or organization receiving any form of support from outside Russia, or considered to be under foreign influence, to register as a ‘foreign agent.’ Unlike the United States Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), which mainly applies to professional lobbyists and political consultants working for foreign governments, the Russian legislation targets NGOs, media outlets, journalists, and even private individuals. A person labeled a ‘foreign agent’ isn’t given a chance to contest the designation in court and usually learns about their new status from the news on a Friday evening, when the updated list of ‘agents’ is published.

Daria Yarzhambek: First, I’d like to say that this was one of those blessed commissions that are really hard to work on. Once you open the file to make some edits, you slip into the text for hours. Even though the book doesn’t contain anything that would otherwise be explicitly censored, it does mention a whole bunch of people that the Russian government has labelled as foreign

Should I add — ‘This material and/or information was created and/or distributed by the foreign agent…’ — right now, set in large type?

After the talk, we read the ‘Law on the Control of Activities of Persons Under Foreign Influence’ and found out that we have to place the yebala even before the first question

Alexandr Gorbachev: I leave it to the publisher to decide. In my own media, which are listed in the Roskomnadzor registry, I put the yebala, yet I do not insist that everyone else does the same.

I would also like to mention that there are still some censored bits in the book, mainly when it comes to drugs. As I wrote my book with due account for the current drug legislation, I expertly tried to avoid the actual names of the drugs. For example, I wrote ‘he first tried the drug that was a symbol of the psychedelic revolution’.

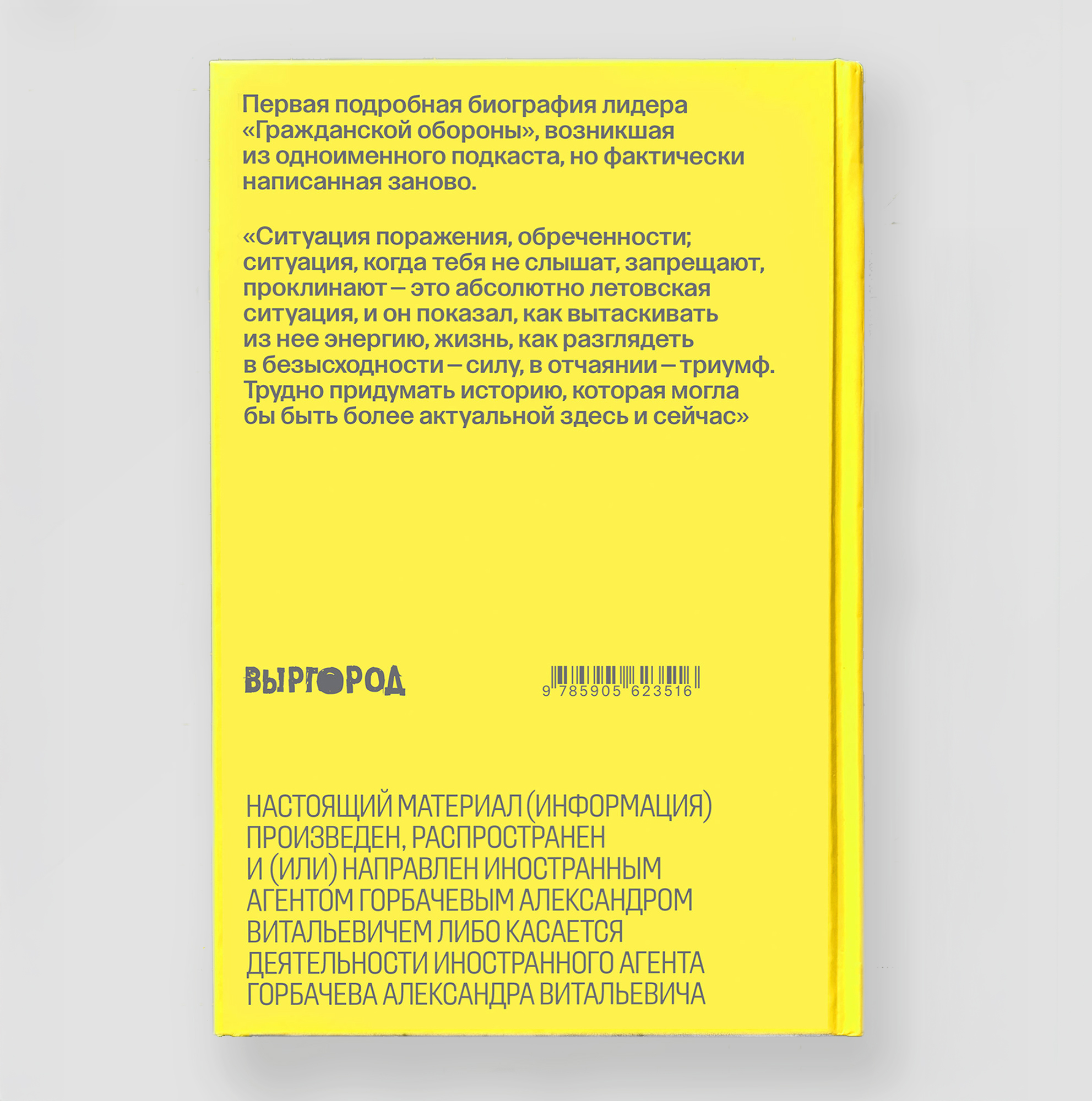

We also had to black out a couple of links to the [so-called] undesirable organisations, as it is illegal to distribute any links of this

Bibliography of the book He saw the sun. Egor Letov and his time

Bibliography of the book He saw the sun. Egor Letov and his time

DY: Why did you choose to black them out? Why this solution, specifically?

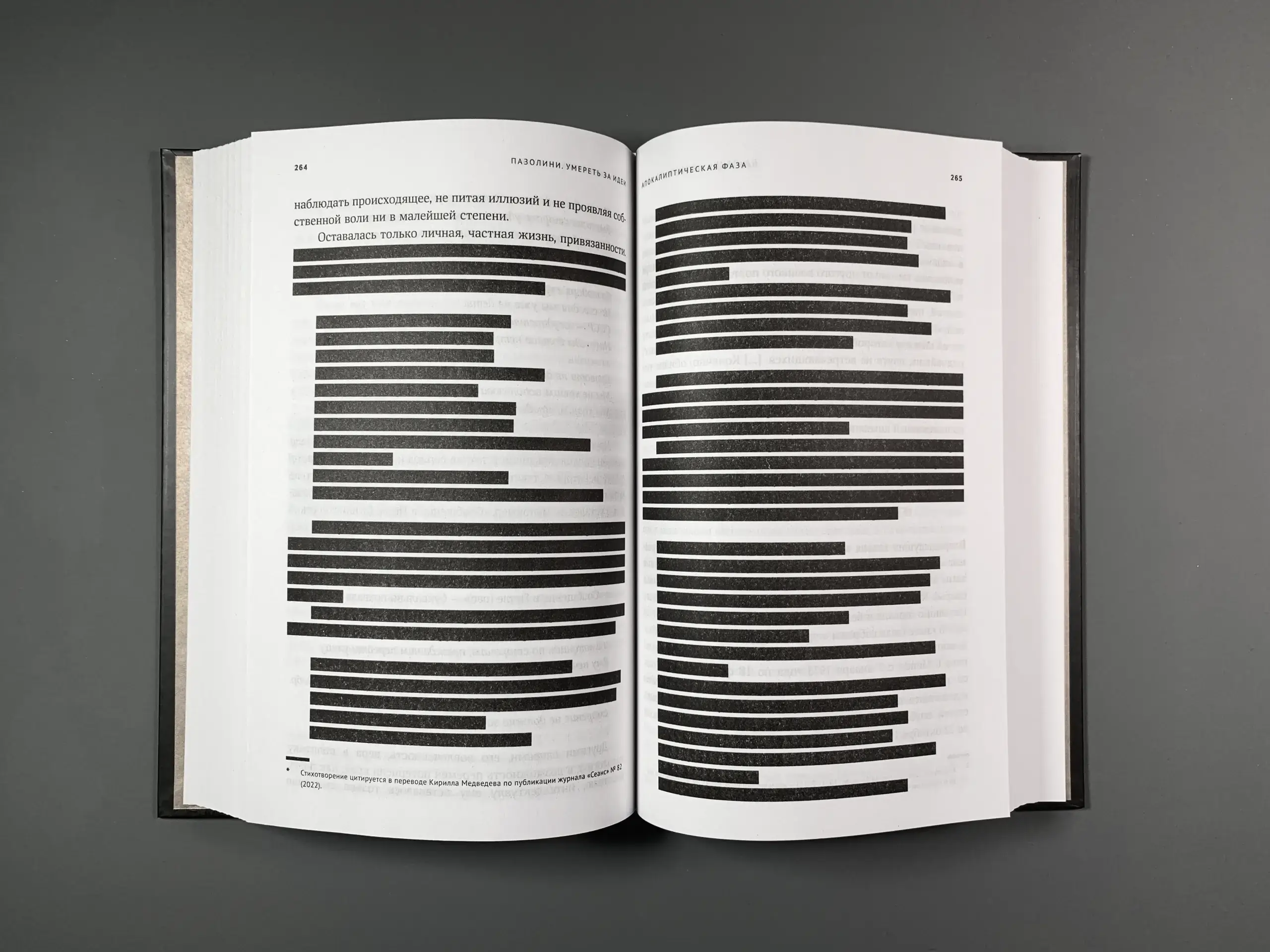

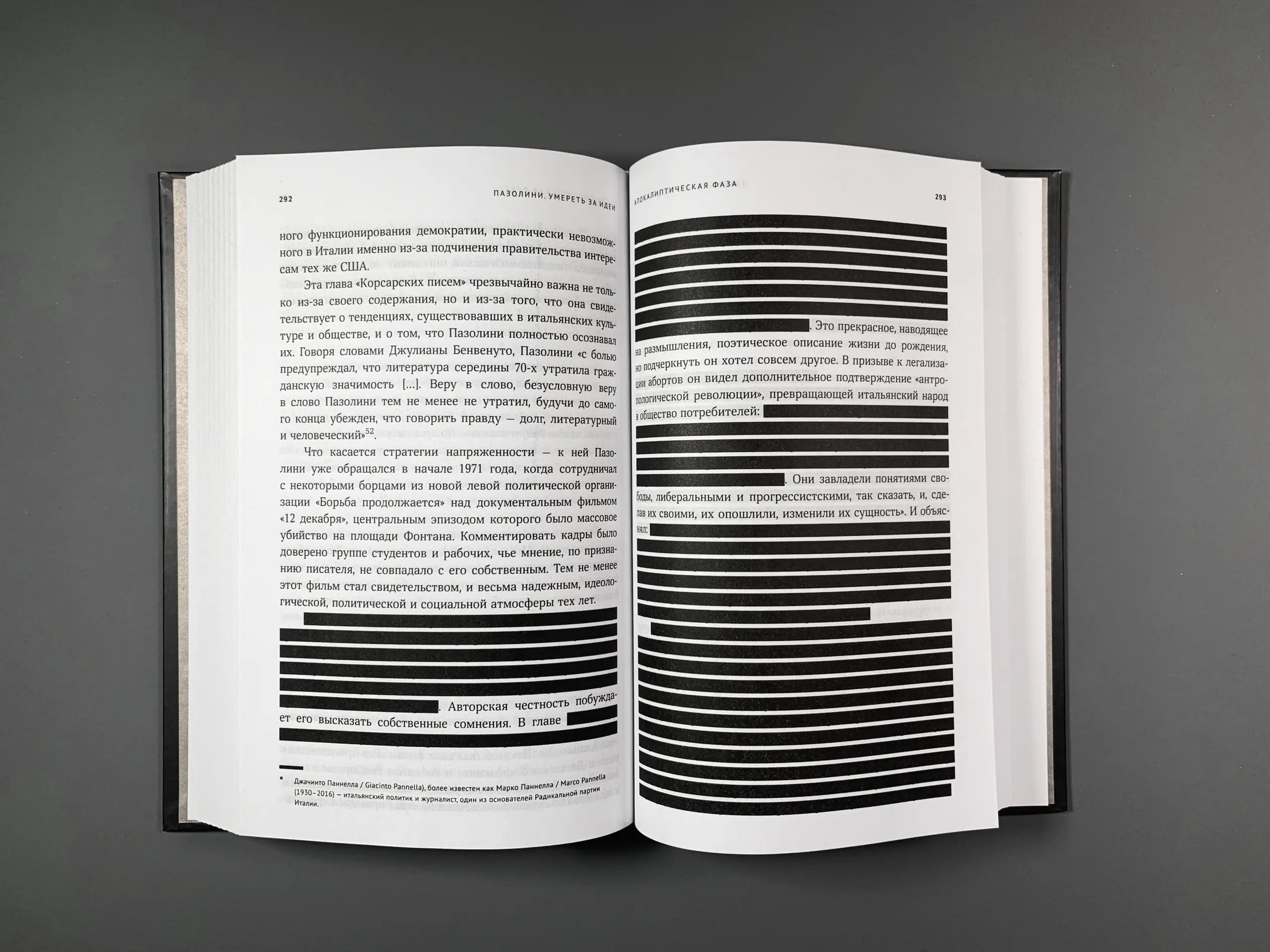

AG: I think that leaving some evidence that the text was edited not because the author or the publisher wanted these changes, but because of the law, is the right thing to do. Other publishers do this, and it catches the eye, making censorship visible. Although, of course, in my book it is probably not as pronounced as it is in Salman Rushdie’s novel or Pasolini’s biography.

DY: I was actually just about to ask you about this case. Well, this book about Pasolini was published, in which one-fifth of the text is crossed out with black bars, and this created quite a stir. There was even

Do you consider the crossed-out pages an appropriate statement? And is it a statement at all?

AG: It’s definitely a statement. Since I haven’t read the book, it’s hard for me to judge whether it has completely transformed into a performance or if some meaning of the book has actually been preserved. In both cases, it seems quite legitimate to me; it’s just that in one case, the book falls into the category of artifacts, while in the other, it is still a book where a significant part is missing. But I believe that this controversy arose because this was the first case like this; now it has become part of the routine.

The publisher Corpus does things like that all the time; you can see it in Rushdie’s Knife, in Michael Cunningham’s new novel, too. From what I gather, this is done with the knowledge and consent of the authors.

The censored book by Roberto Carnero Pasolini. To Die for Ideas. AST Publishing, 2024. Image: Podpisnye Izdaniya

DY: How long do you feel this will go on like this? Is it the routine we will have to deal with as long as there is censorship, or will all these elegant

AG: When it comes to this particular move, it seems like it cannot really be banned. Then again, we’re talking on September 2. Yesterday, a law came into force banning foreign agents from being engaged in any educational activities. Nobody knows yet how exactly this legislation will be implemented. The educational activity is defined in such a way that literally anything fits this definition, including a Facebook post, let alone non-fiction books.

We’re now seeing a kind of grey area

Before the law came into force, many bookstores and publishers held garage sales where they sold off the books of ‘foreign agents’. The photo shows a sale by NLO Publishing. Image: NLO social media

Before the law came into force, many bookstores and publishers held garage sales where they sold off the books of ‘foreign agents’. The photo shows a sale by NLO Publishing. Image: NLO social media

It seems to me that there is some kind of irritation in place about the fact that ‘traitors to their nation’ still allow themselves to speak publicly within the country, which means that somebody listens to them. And they are now trying to put an end to this. But now, I believe, it all comes down to how this new legislation will be applied to the book industry.

There is a number of precedents: a case filed in the spring against Individuum and Popcorn Books, searches at Falanster and Podpisnie Izdaniya. If this trend continues, if they keep removing books by foreign agents from bookshops, it is likely that they will come after publishers, too. They will ask, ‘Why the hell are you selling books written by foreign agents, who are banned from writing?’ Then the publishers will be more

DY: When all these laws requiring you to put a foreign-agent disclaimer first arrived, there was a lot of bitter fun. For instance, there was this flashmob when designers came up with some fancy designs featuring this absurd text, while others accompanied the yebala with witty musical bits if it was a video…

Your text — the one that describes how we reveal censorship in the

The text mentioned by Daria lists the individuals in the book labeled as ‘foreign agents,’ along with all the organizations and media designated as extremist or otherwise objectionable by the Russian Federation. It also includes disclaimers stating that suicide is never a solution and that drugs are harmful, these disclaimers are also legally required

AG: The other day, Blueprint posted a pretty great piece in which a book critic recommends books written by foreign agents. At the beginning of this publication, they added a massive label listing all the foreign agents featured in the article. So, when you scroll this piece on your phone, the label also goes on and on, and it produces a really strong effect on you, making a really powerful impression. Everything is done by the rules, but you can tell that this is a deliberate absurdisation of what is happening.

In my book about Letov, there was indeed a long list of foreign agents, as well as a long list of matters related to extremism, suicide, and drugs. Perhaps the only person we should thank for it being so comprehensive in that regard is the book’s protagonist himself, who managed

This black dot is a really great move, I think. When I first saw it, it made me think of this meme, the angry dot. This ‘angry dot’ kind of demonstrates, through its shape, the author’s attitude towards it.

DY: Between us, we referred to it as ‘the black mark’. I’d like to confess that we actually had some inspiration: while we were working on the book, there were people protesting against the outcome of the election on the streets of Tbilisi, and the heavy black dot was the symbol of that protest. People drew it on their white flags, on their armbands.

This was in response to a situation when people at one of the polling stations were marking ballots with a black marker pen, which showed through the paper. Activists filed a lawsuit, as it was a violation of the vote confidentiality, and, clearly, lost. At some point, we were seeing lots of these black dots around us. I don’t know whether it’s appropriate to call a protest symbol beautiful, but if it is, then I believe this was a great one.

AG: Yes, that’s a good one.

The black mark on protesters in Tbilisi. Image: Georgia Today

DY: My approach to visualising censorship restrictions is this: the worse, the better. That is, if we are to put eight foreign-agent disclaimers on a page, then we will put all eight of them. But at some point, you said that that was not okay. Why?

AG: Because I think the reader’s comfort is important. This marker makes you still keep in mind that there’s censorship in place, but at the same time, it doesn’t interfere too much with the text.

If the footer were made up entirely of three yebalas, they would actually claim the entire space of the text for themselves, and I wouldn’t want that to happen.

DY: You were writing the book that you were going to publish in a space of non-freedom, whereas the concept of inner freedom is the concept that often comes up in connection with your book’s protagonist. How did it make you feel?

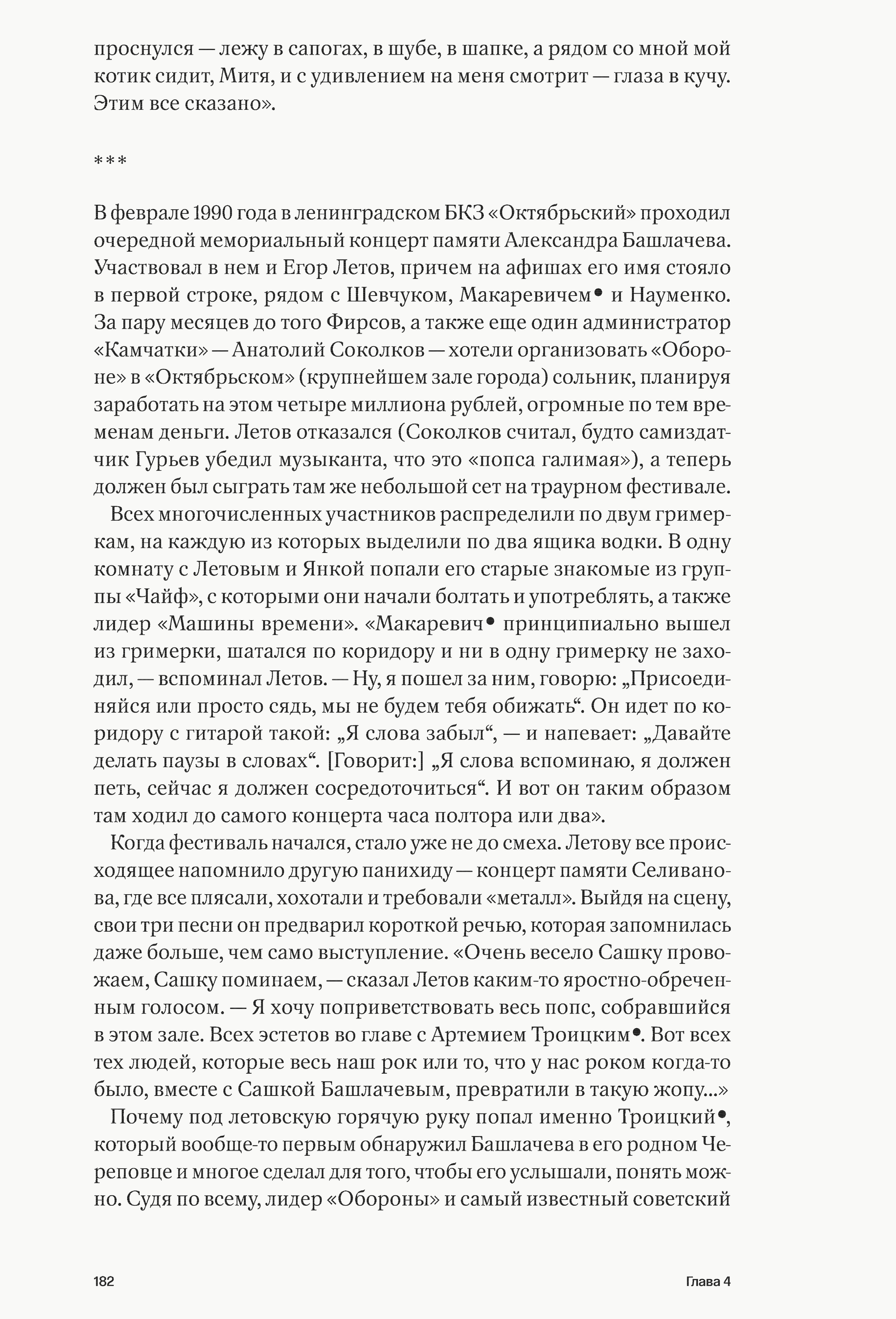

AG: Letov consistently stayed in the most uncomfortable space. And here I am not even talking about Russia, I actually mean Omsk, his GrOb studio that didn’t resemble a professional recording studio in the sense in which this term is normally used in the West. Letov, on the one hand, always remained within these boundaries, while on the other hand, he was constantly pushing these boundaries.

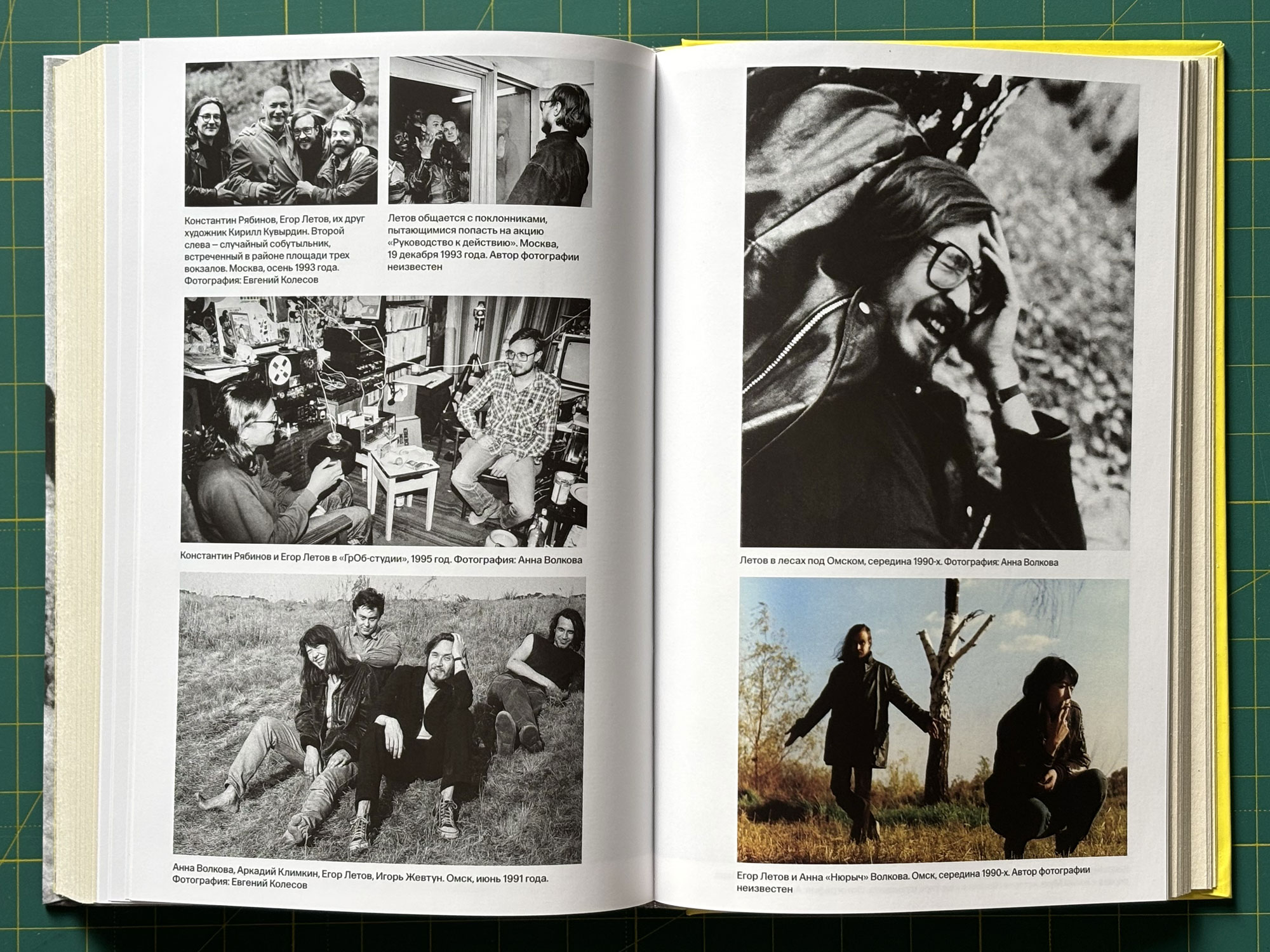

GrOb studio. GrOb is an abbreviation of the band name Grazhdanskaya Oborona (Civil Defense), probably Letov’s most famous project

When it comes to music, he was literally flying into space out of the space of his room, using Ilya Kabakov’s metaphor. And on some level, it was important for me to do the same. I understood that perhaps I could have brought this book somewhere else and had it published, but it was important to me to publish it in Russia. I consider it as asserting my right to speak.

Meaning, the authorities want to silence my voice in this space, but I will speak out by any available means as long as it’s possible. Now the space has shrunk once again, which means we will need to come up with something else.

DY: Let’s get back to your own foreign agency. I meant to ask you how you personally handle the yebala? How did it fit into your texts?

AG: That is really funny. I was initially worried about how it would fit into my music-themed Telegram channel, where I post short reviews. In this format, the yebala often ends up taking more space than the text itself. But, frankly, it fit

It’s interesting how it all worked out with my social media. In a way, I even benefited from my foreign agency as I became less likely to get involved in meaningless online discussions. Once I start typing something, I immediately

On the other hand, at some point, I started considering this disclaimer as some sort of joke. For example, I might write a comment about something completely trivial, such as food, and put the yebala next to it. I do realise that there are people who perceive this thing as a yellow star and suffer a lot, but I tend to use it as a carnival element.

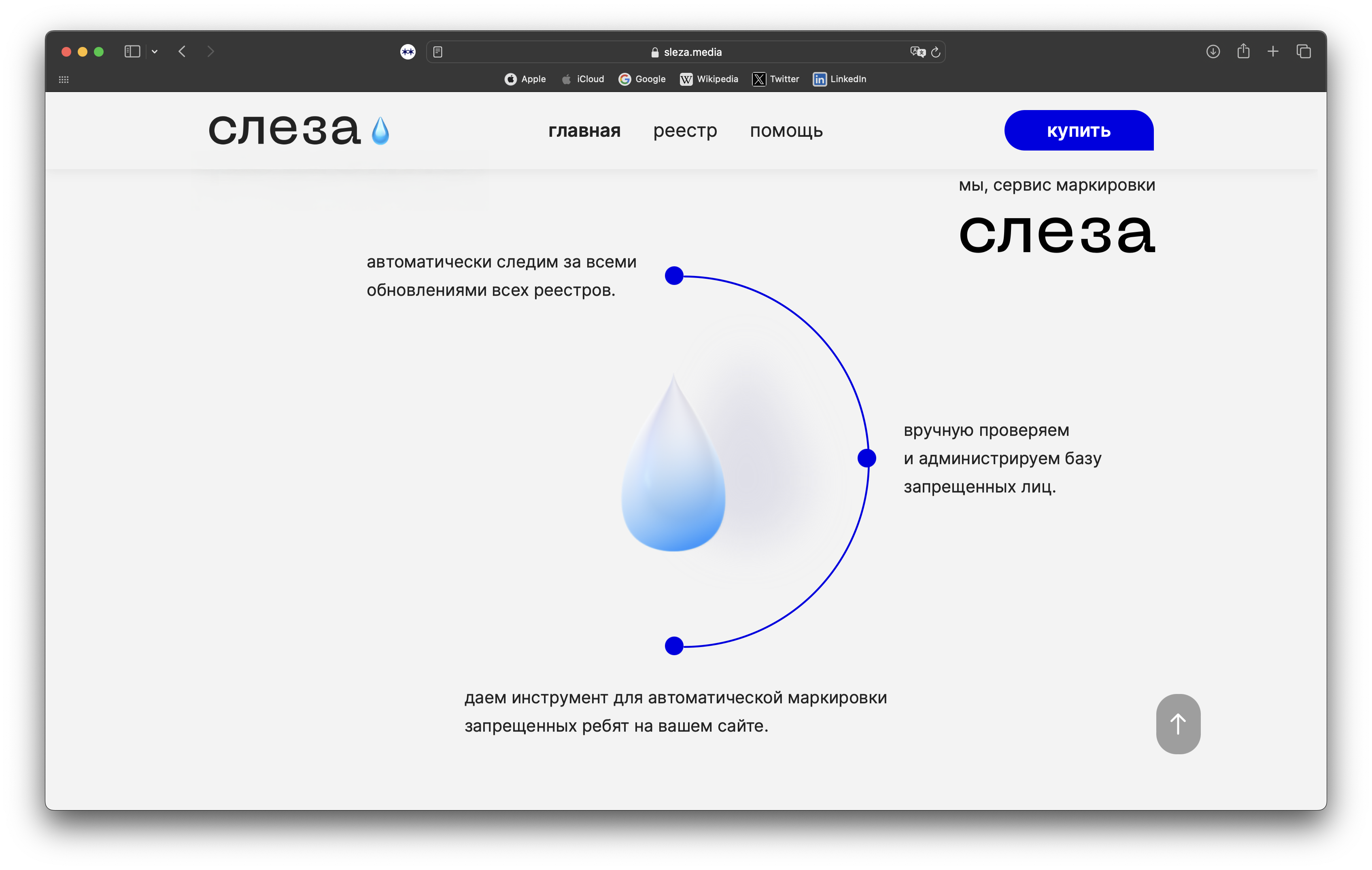

Website of the ‘Sleza’ service. The service constantly monitors the lists of undesirable organizations, foreign agents, and extremists, and offers media outlets and blogs a script that automatically marks such people and organizations with a tear emoji

DY: So, you think irony is still appropriate?

AG: I believe that the situation we’re in right now proves that irony and laughter are always appropriate and relevant, and can be deployed in even more horrific situations. There’s something Letov-like in all this,

DY: Do you have an idea why most people capitalise the yebala, even though the law does not require it?

AG: The law states that it must be larger in size than the text itself. Of course, it does not specify that it should be set in all caps. I think it’s just that everyone is copying one another.

DY: Let’s talk about your publishing project. We could call it a publishing project, right?

AG: Yes, a publishing initiative, a publishing

If only this term didn’t carry these idiotic pop music connotations, you could have called us a production center. We combine the roles of a publisher and an agency, all while being a non-profit organisation. On the one hand, we help authors write non-fiction books, which are currently impossible to publish in Russia. On the other hand, we help get those books published in different languages; that is, we approach publishers and negotiate with them.

But we are a nonprofit — we don’t take anything for ourselves: all the rights remain with the author, and it’s also they who get all the money for all the books. I can now say that we produce great books that have a successful life, in one way or another. All three books we’ve published made it to the long list of the Enlightener Prize. We’ve finally picked up the pace and will soon start publishing more books.

But it is a bit more complicated when it comes to fundraising. We started with the money from my partners, Alexey Dokuchaev and Felix Sandalov, and we also received some money from donors, as well as attracted some grant funding. Yet whether we will still be around in a year, no one knows, since so far we have not been able to bring in any stable financing.

StraightForward website

DY: Do you get to the design stage with the authors, or is it a publisher who is in charge of this?

AG: Publishers are in charge of this; we have more of a consultative vote here. I don’t get involved in that much myself, since I have enough to work on when dealing with the text. I believe that even if our opinion on this is relevant, it’s only with Russian-language publishers.

DY: Do you know how hard it is to find a designer who is willing to design books that will be banned in Russia?

AG: I feel like there are plenty of designers. This is a creative profession, after

Most of the designers I know have left the territory of the Russian Federation, so I don’t think it’s hard to find one, especially since design can remain anonymous much more easily than text. An author can adopt a pseudonym, and then people will treat it just like a real name, whereas a designer may choose to leave their name off entirely, and it won’t raise any questions.

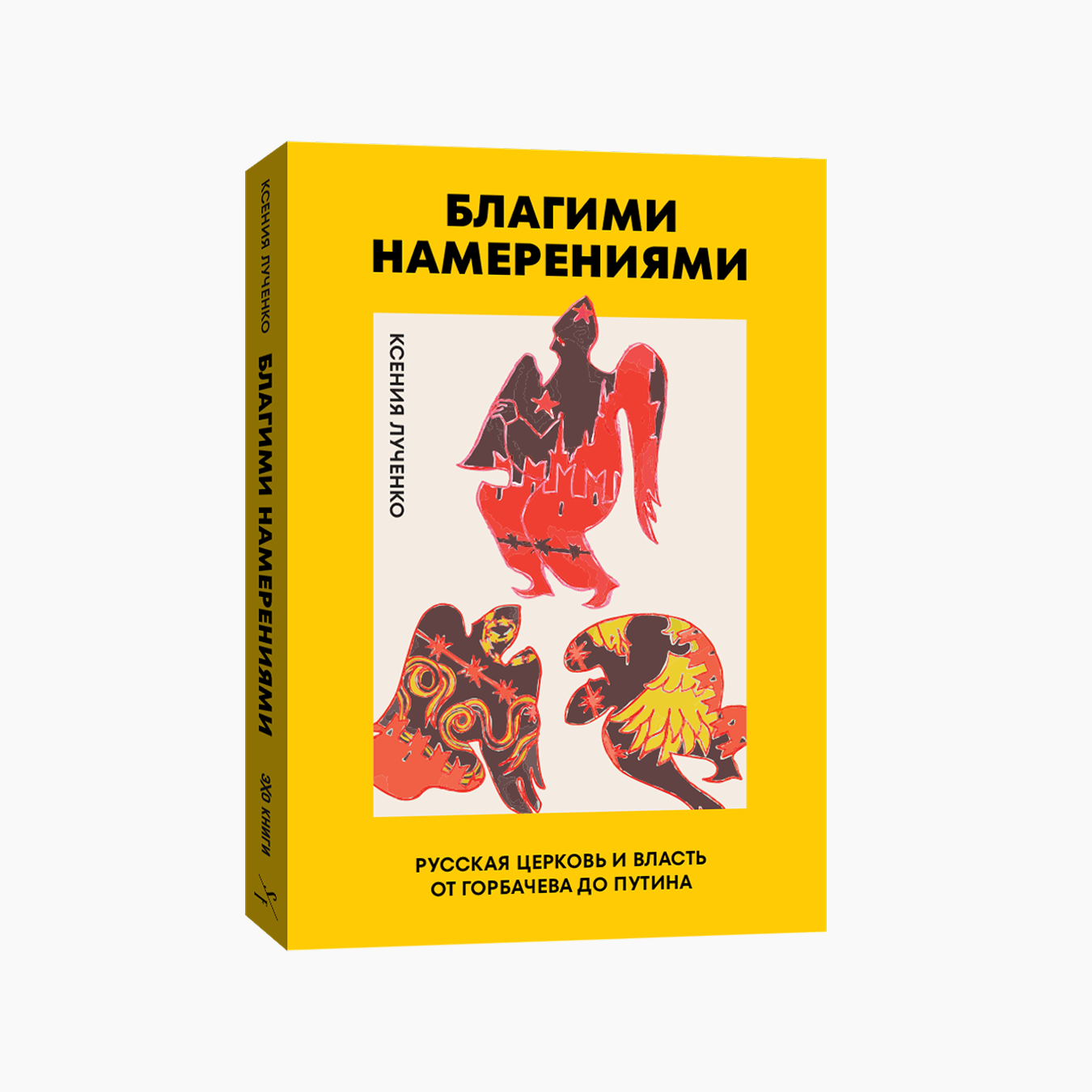

Books by the StraightForward ptoject

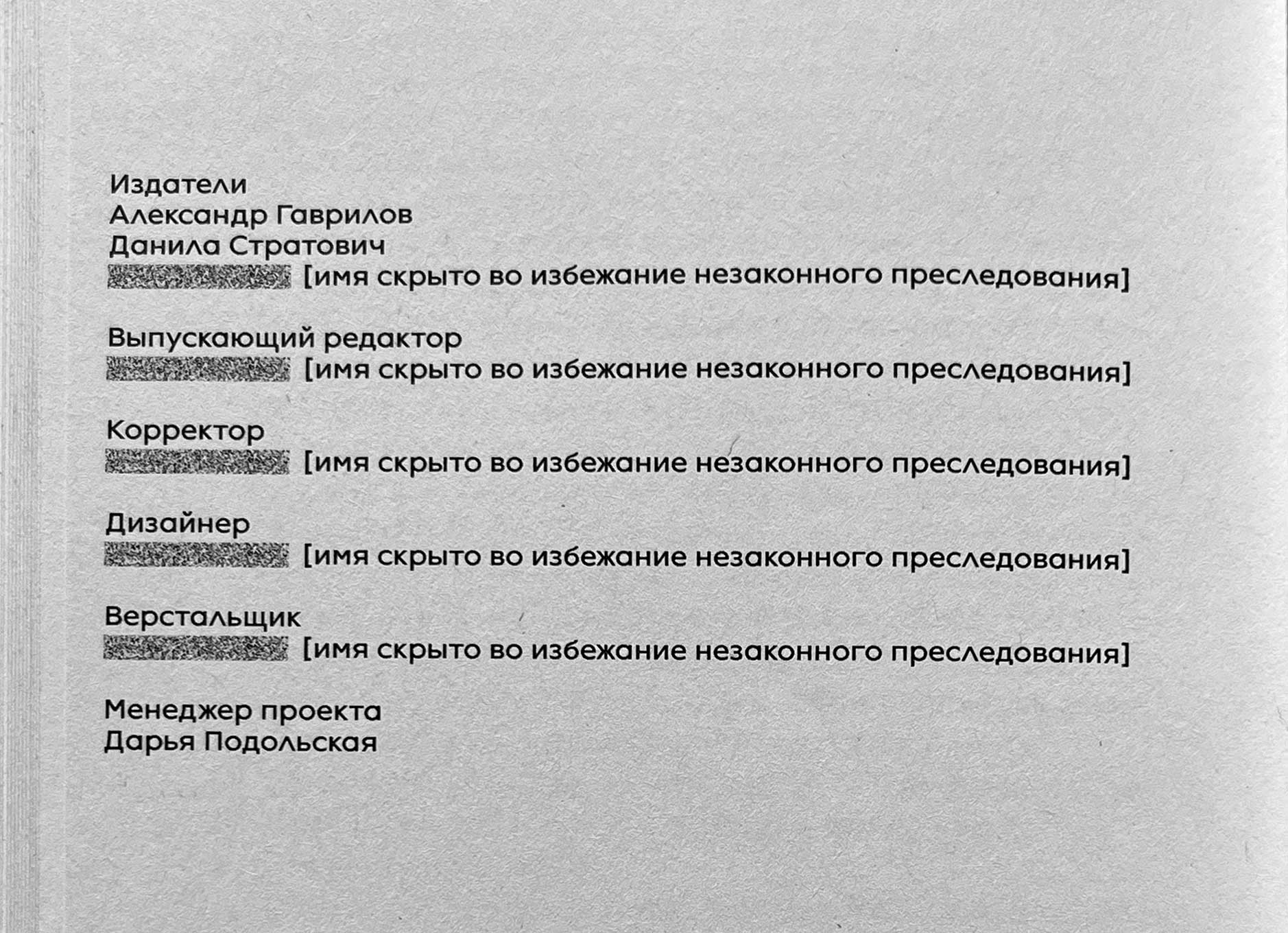

DY: I have a book where the entire team is blacked out. Also a kind of censorship practice.

AG: Yes, a kind of reversed censorship, to avoid risks. It happens that our fact-checker chooses to sign only with their initials. Quite often, an editor or a proofreader, who is clearly based in Russia, won’t use their name in a publication, and it is somehow solved graphically.

Colophon of the book by Vidim Books publishing house

Colophon of the book by Vidim Books publishing house

DY: Please tell me, is there at least some silver lining to this dark cloud?

AG: I do not think of it as a dark cloud. I believe there is something marvelous about the very fact that people read books. All of a sudden, it proved to be the medium people actually need.

As it turns out, we need those