Each designer has their own distinct type experience — each has their own tastes, their own personal typographic skills and experience with type stores. We spoke with Alexei Murashko, a graphic designer, typographer and art director of the VCG agency (Riga), and composed a monologue on font expectations, dreams and reality.**

Being a frequent visitor of font shops, I have accumulated a great many questions for them, though I mostly end up talking about it to myself, having nobody to share them with. It is even harder with Western font designers, despite the fact that they seem open to comment. But my personal experiences have not been very positive in this regard.

Of course, the worst that can happen when buying a font is when you go to the store, pay for a font you need right now, and you are sent a letter stating that the application has accepted and the font will be available after some time, or else that they will contact you later. This happens only rarely, of course, but it does happen.

It’s also inconvenient when a store refuses to accept a European bank card. This mostly happens with Russian platforms. We have occasionally had to look for alternative payment methods because of this, making a direct transfer to the account, paying a decent commission. And I understand that there are technical problems sometimes. But in this case I have to solve them myself, just because I really need a particular font with Cyrillic.

On the prices of fonts

I am willing to pay for fonts, and in some cases am even prepared to part with considerable sums by the standard of our budget. When buying fonts with Cyrillic from Typotheque, we pay 120 euros for the typeface, with admitted reluctance. We purchase a package of two or four typefaces, rarely taking more due specifically to the price. But there is also a plus, because we are perfectionists, and don’t need much: we are quite capable sometimes of managing with just one typeface with a capital in a given project.

For us Europeans, VAT is an extra thing that matters. If I, as an individual designer, a freelancer, buy fonts and pay with my card, I have to pay the value-added tax when I buy from the major sellers (Myfonts, Fontshop, and Linotype). This means that the price of the font is automatically increased by 21%, which really is an appreciable difference. It’s simpler for the companies, of course. They are issued European invoices tax free.

Among other things, the difference in the approach to pricing between American and European font foundries also matters when buying fonts. Fonts of similar quality made in Europe are, on average, 30-40% more expensive than American ones. And then you have to add to this the VAT, further increasing the difference. And we don’t need to pay VAT when buying fonts directly from the Americans, or from Russians, for that matter. Russian and Ukrainian designers, and Central European designers, as a rule, have very competitive prices, but don’t always have what’s needed. If we are looking for something up to date, we often find it in the West, but much more expensive.

There are situations where there are completely different conditions for licensing a font by purchasing it directly from the manufacturer or through a large distributor. When you buy a web license from MyFonts, it costs so much. Exactly the same license, purchased through FontShop or through someone else, will cost something else, or it might have different conditions for the number of unique visitors to the site. This enables you to seek out the best offer and sometimes save money.

I’d like to say something specifically about those situations when a store makes me pay for Greek as well as Cyrillic. This used to happen more often in the past, but it still happens now and then. You can’t buy the Cyrillic separately, it’s only sold in a set with Greek, serious adding to the price. The number of Greek speakers is incomparably small when compared with speakers of languages which use Cyrillic. I know why these two character sets often go together in the Western world: they’re used in typesetting encyclopaedias, where it is very important to have the entire character set. Or in religious literature.

Of interest to Cyrillic users of the Pro button in the typotheque.com store:

Of interest to Cyrillic users of the Pro button in the typotheque.com store:

But I live in a small country where the budgets are rather less generous, and the salaries more modest. And so we pay more for the fonts than anyone else, because we need the extended Latin alphabet, and often the Cyrillic too. You end up with a situation in which the Dutch, who have no need of any of this, pay 90 euros for a typeface from Typotheque, while we pay 120 for the Pro version, using budgets that don’t even come close to the capabilities of the Dutch. And this isn’t even the most drastic price difference I’ve seen, sometimes it’s even more. We are in worst market situation and so we are forced to agree to all conditions. Otherwise we wouldn’t buy anything up to date and would be forced to keep choosing old fonts from the ParaType collection, with all due respect to it. And its current state, unfortunately, is very far from anything you might think of under the term “todayness”.

On the peculiarities of relations

I have many times heard the phrase: “Look at the font as a tool” from Russian font designers of both the older generation – and often from the younger, too. But if you regard a font as an instrument, then maybe it’s worth trying to clarify the terms of its sale and its possibilities for me… If I buy an axe at the hardware store, I can sharpen it, replace the handle, paint it or wrap it up with duct tape. Back in the days of hot-type composition, you could use a file to whittle away at the sidebearing, and if you really wanted to you could cast your own version of a letter. But you sell me, or rather license to me a font whose terms of use are severely limited from the get go. Few objects of copyright have as many restrictions on use as fonts do. And this is even the case with the most democratic licenses like the old ParaType license, never mind the stricter ones. And it’s especially true of the Americans.

So it turns out that this is like a tool, but a tool with a whole bunch of limitations: I can only use it in limited ways, it’s often forbidden to use it in titling, and sometimes on T-shirts and other merchandise, and modifications are prohibited with rare exceptions. In general, I have to accept it as is, and if I don’t like something in it, I “have the right to choose any other”. In Cyrillic, for example, where choice is very limited, and is simply not present at all in some style segments this seems like sheer mockery.

Going further, we have problems with the purchasing: sometimes you have to make super strength efforts to make a purchase. To persuade them to sell it! Calls, letters, negotiations… That is, I want to pay you, and I have to put in immense effort to give you this money! This is stupid and crazy. Font sellers used to want to look the buyer in the eye. It seems to me that if you are doing this as a business, the buyer’s eyes should not interest you at all. You should only really be interested in the buyer’s obligations to you and their compliance with them. If there seems an issue with that, then we have the market mechanisms of various restrictions – licenses and pricing. Fortunately, this phenomenon is now being overcome quite quickly.

On artists and businessmen

If you want us to treat font designers not as artists, but as professionals for whom this is a business, a way to generate income and provide for yourself and your family, then it would be worthwhile (I say nothing of “should” here, this is only some advice if you want to earn a living) that you yourselves treat this as a business where there is a consumer with needs and requests. Otherwise, this transforms into a situation of font experiments, or one where fonts are made only for personal use, or where highly promising projects are never brought to culmination but just disappear into oblivion. Sometimes it seems that some typefaces are intentionally being hidden from us. Apparently they’re afraid that they will be stolen, and that’s why they don’t sell them to anyone, making them just for corporate purposes.

As an example, you may recall the history of fonts connected with the graduates or the teacher of the “Font Workshop”. In my list of universal fonts which still haven’t lost a feel of “todayness”, there are two Alexander Tarbeev fonts: Big City Antiqua and Afisha Serif, which is Gauge. Two fonts whose equals I have not found for their performance in their Cyrillic styles. I’m still waiting and hoping for their release. Two decades have passed.

Afisha Serif or Gauge by Alexander Tarbeev

Afisha Serif or Gauge by Alexander Tarbeev

Afisha Serif or Gauge by Alexander Tarbeev

Afisha Serif or Gauge by Alexander Tarbeev

I wanted to make a special mention of a doubly sad history, because it’s a human tragedy and a great loss; the font legacy of Artem Utkin, who managed to make several sets for his small but rather intense creative life. His Solution – on “Modern Cyrillic” in 2009 – won a diploma, and special mention from Yefimov (Vladimir Yefimov, 1949-2012, font designer and art director of ParaType – Ed.) who was sitting on the jury. I once corresponded with Artem about the possibility of acquiring a font, but it didn’t work out, unfortunately. He wrote that the font was too raw. He also had a second font – Metro – which is terrific. At the time when it was created, it met the criterion of “todayness”, mentioned in every conversation of this series, fully. And I’m very sorry that this family, with its well-developed typefaces, has remained inaccessible for use. I would be delighted if any enthusiasts out there could help release these fonts and give them life. I would definitely use them.

Artyom Utkin’s Solution typeface

Artyom Utkin’s Solution typeface

Like any good artist, a font designer should probably have an impresario or agent. And yet there are often font designers now who’ve been able to build up the business side well, and I can bring up examples of those who may well have outgrown the role of designer – such as Bilak (Peter Biľak, font designer at the Typotheque studio – Ed.). He came up with a great deal of things in terms of sales mechanisms, and they work. His fonts are desirable purchases not only because of their quality, but also because the buying process is as simplified as possible. He seems to have been the first to come up with a license for web fonts with a limited amount of page visits, simultaneous with the purchase of the desktop version. In some projects this has helped us to make considerable savings. Otherwise we would’ve had to pay decent money for individual web licenses.

On renting fonts from Fontstand

Fontstand is a good initiative and very useful. At the present moment, I have a few comments for them, the most fundamental of which is the lack of a Windows version. This belief that all designers must necessarily be users of the Mac platform seems strange and obsolete to me since the late 1990s. And so it turns out that Fontstand is unsuitable for a significant number of designers who probably would have used it. But we have a few Macs in the company, so Fontstand is worth it and is used to assess the quality of the font and the rhythm of the character set before buying.

I would definitely like to have a more detailed and branched structure of parameters when choosing fonts on these services (bearing in mind that Fontstand’s library has grown several times since its launch). Bilak mentioned that they hired Indra Kupferschmid, who came up with an updated classification for Fontstand, something similar to ATypl and Maximilian Fox’s classification. But in reality it turned out that it wasn’t detailed enough. And there are a few glitches in places. For example, the Brioni Text Pro font is linked to the “slab” tag because of the squared serifs and is displayed in the corresponding selection, while the ordinary Brioni Pro, that’s slightly less squared, is not. Besides, this is just one type family. It’s good that I know the composition of this set. But other designers will find it harder to cope with such situations, and simply may not find the font.

On choice and quality

Perhaps we suffer more from an excess of choice, with regard to Latin fonts, than from the opposite. In some style segments (for example, in geometric grotesques - from Futura to Erbar), the range on offer has become so huge that it’s hard for us to choose at first glance. And then you have to factor in the additional criteria: the x-height, the proportions; to take into account the peculiarities of the forms of symbols. Sometimes fonts look strange and ridiculous in the Latvian set of diacritics, and so some of the fonts are automatically ruled out. But, as you know, I can’t put them all on my computer to check this. We have to spend time looking, downloading specimens and considering glyph lists. And there are still some serious high-quality modern text sets with Cyrillic that I can only buy from a small number of Western designers, with rare exceptions. It was literally here, at some point, that I discovered that the freshest text fonts with Cyrillic which I want to work with are made by native speakers and specialists who understand the Cyrillic alphabet, but for Western type foundries. Thanks are due to Bilak, who seems to have been the first to start this systematically and continues to do so. I wish the good manufacturers would invest into Cyrillic and other scripts, as he has done. Few have done as much for modern Cyrillic text as Bilak has and, to a lesser extent, Nikola Djurek. It’s sad because it’s not enough, but it’s good because there are at least these two.

There are so many fonts coming out that the only criterion for selection for me now is whether or not they have Cyrillic and extended Latin. And this situation is quite unusual for Western designers and typographers. The book designer Tom Mrazauskas from Lithuania, a colleague and friend of mine, says: “If I don’t like a couple of characters in the font, I just switch to the next one.” In his case, there are no problems: on FontStand, which he makes considerable use of, there are all these geometric grotesques which are not going to go out of fashion, and they’re a dime a dozen. Don’t you like it like this? Would it be desirable if the lower case was bigger? You’re welcome. Do you want it a bit rounder, or more human in feel? You’re welcome. A million options, and they continue to appear. But not for me. My situation is starkly different.

The query “geometric grotesque” on the Myfonts.com search engine yielded 453 results at the time of publication

The query “geometric grotesque” on the Myfonts.com search engine yielded 453 results at the time of publication

For me, a contemporary font is one that is technically executed with quality and, in the most magnificent cases, with some extra additional quality to it. And it’s hard to give an unambiguous criterion of what this quality is, though for me the fonts in the full OpenType set of features are very important, and, of course, the small caps. You can leave aside arguments about the need for small caps in the Cyrillic set for Russia. For me, in my context, it is absolutely necessary. For me, if a font has small caps, it automatically increases the number of typographic methods for text processing, in some cases twofold. I can make a book with a single typeface, and it won’t look boring thanks to this.

As for those who remain convinced that small caps are not needed in Cyrillic, okay, God bless you. I’m not talking about all fonts – it would be strange to ask for small caps in printing works. I’m talking about working antiques and text grotesques primarily, with which you can produce various different books – which, as many believe, have become obsolete. In my practice, they have no intention of dying off yet, so I continue to make them.

On the fonts that exist

If I want to make a book, for example, of an academic nature, but would like it to have a “today” appearance, I can choose from a very small number of fonts. Because I live in a country where we still use Russian to a certain degree. Most of what we work on as a studio is bilingual or trilingual materials: Latvian - English - Russian, Latvian - Russian, or Latvian - English. And the books that I make as a book designer, as a rule, are also multilingual. This means that I need all three alphabets, and if a font doesn’t have them, then usually it’s automatically beyond my range of interest. The criterion has developed over time. And then you go around, smacking your lips at these beautiful new fonts, but they rarely work. I postpone some things, though. I dream about it and expect to use them one day in some book, where Cyrillic is not needed at all.

My list of Cyrillic fonts which I consider universal or moderately universal, without any very pronounced historical smell, comes somewhere to the figure of a dozen sets, of which a large half are modern Western fonts. I’m talking about antiqua here.

These are Lava and Brioni Text, which I really like, and I will make the next book with them. This is William by Maria Doreuli (Maria Doreuli, font designer at Contrast studio – Ed.). William is beautiful. It’s a bit darker if you work on uncoated paper, but still. If our world does not perish in a nuclear catastrophe, it seems to me that this font will outlive both me and Maria. It’s too good, surprisingly good for a diploma work.

William Cyrillic has not yet been released, but work on the final version continues

I really like Neacademia. I have heard conflicting reviews about it from designers in Russia, but for my small niche I liked how it was made, and the set looked interesting and good. Although, perhaps, this is an exception to the list of universal fonts.

Charter has faded a little in Russia, but not in my context. I used it for a while as a magazine set, when I was working in Russia, and I think that this is still a font with great prospects. And it is contemporary, with not too explicit a character, and is suitable for everything: it can be used for literature, academic publications, academic publications on economics – for everything.

I also like the classic SchoolBook typeface from ParaType library, of course. I consider Kazimir as some kind of stylistic branch off of this. I understand that it was based on a different kind of logic, but for me, as a printer, this is by and large a more decadent or more libertine version of SchoolBook.

And there’s ITC New Baskerville, of course. I would definitely include it in the top 5 Cyrillic fonts of all time. I really like the ParaType version. It was canonized as a universal font for me by Vladimir Krichevsky in his Typography in Terms and Images – as his immortal creation, which surprisingly, in my opinion, due to the progressiveness of the layout itself, does not manifest but even conceals the historic nature of this font.

This is Original Garamond from ParaType. It doesn’t suit everything, but this is a trivial matter considered in comparison with other fonts.

At the time, I was surprised that Typejournal.ru magazine chose Kis for their publishing projects. I didn’t like this font and it didn’t seem very easy to read. The Cyrillic had a pronounced historical character, which automatically makes it less attractive for me as a typographer. The more dated a script is… and that reminds me, the Cyrillic in Filosofia is very historical, it is very hard work, while the Latin is very fresh – quite an amazing story. I did the last book I’m going to print tomorrow in Filosofia. And it was chosen because there was Cyrillic there: a small amount of citations and footnotes on literary sources had to be printed in it. While the main text in the Latvian language looks quite modern.

Vladimir Yefimov’s Kis from the ParaType library

Vladimir Yefimov’s Kis from the ParaType library

Vladimir Yefimov’s Kis from the ParaType library

Vladimir Yefimov’s Kis from the ParaType library

Vladimir Yefimov’s Kis from the ParaType library

Vladimir Yefimov’s Kis from the ParaType library

Vladimir Yefimov’s Kis from the ParaType library

Vladimir Yefimov’s Kis from the ParaType library

Vladimir Yefimov’s Kis from the ParaType library

Vladimir Yefimov’s Kis from the ParaType library

So there you go, I was surprised how much I immersed myself in Kis when I started reading in it. It seems Zuzana Licko (Zuzana Licko, typeface designer at Emigre studio – Ed.) said that we love most what we read most, referring to fonts. When I read the typed material in Kis… it was an article by Yefimov, published in pamphlet form, one of the first issues of TypeJournal.ru magazine… I read it through and then read part of it on the screen from their website, and I felt this sensation of mustiness and the antiquarian.

There’s a small group of headsets from Adobe: Arno Pro, Garamond Premier Pro, and Adobe Text Pro. Ah, and Georgia too, especially since the emergence of the Pro-version with OT-features.

It turns out that if you take away the historical ones from the fonts that I have listed, those with a vivid character, like Garamond and Baskerville, the choice is very limited.

You might also recall the Chetverg font that Otadoya made (Otadoya is the studio of Yana Kutyina and Andrei Belonogov – Ed.), but it’s not been fully licked into shape yet, in my opinion. It needs another going over. Just like Maria Doreuli remade her William, and did it quite well. If you looked at it again and twisted it just right, you’d get an excellent Russian analogue of Arnhem.

Chetwerg by Andrei Belonogov

Chetwerg by Andrei Belonogov

On the fonts that don’t exist

I’m terribly short of contemporary fonts – primarily for Dutch and then French. There is a certain amount of amazing antiques, which I want to work with, but which have no Cyrillic. Here’s a rare case: I will soon be doing a compilation of scientific materials in English, typesetting it in Lyon and I feel great because I don’t have to worry about the Cyrillic.

Of course, I’m a big fan of the Dutch and their font heritage, and I’d love to have Arnhem with the Cyrillic alphabet. I would like to have Lexicon and Trinite in Cyrillic from Enschede, and Albertina and Elzevir from DTL. This is absolutely impossible, but one can dream. FF Scala, Ms. Eaves and Serapion too. Perhaps Stanley would be nice in Cyrillic. I’m always shocked by those fonts in which the designer has laid several visual layers. The story with Stanley is wonderful. I went to Leipzig last year at Christmas and saw a poster typeset in an incredible font. It was a poster for an orchestra, which had chosen Stanley for its corporate identity and uses it for everything, and even on its website. I only later found out what kind of typeface it was. I particularly liked how in the large-size composition set on a city-light all the distinctive features of this font were made to stand out so much that it acquired a completely different tone in comparison with the font sizes. And in the small size, it’s so calm and even. I think that this is just an excellent example of a font with added quality and a breadth of possibilities.

A poster typeset in the Stanley font. Photo by Alexei Murashko

A poster typeset in the Stanley font. Photo by Alexei Murashko

Fleischmann is also a special case. It only exists in a decent form at the Dutch Type Library. In fact, this is the only Baroque font in which the aesthetics is expressed in as concentrated a way as possible. The intensity is lower in Baskerville, which is somewhat more reserved and English. While Fleischmann is a real royal celebration. It’s as though you’re watching fireworks going off, ice statues draped with oysters and desserts, and good wine sloshing into the glasses. I get a feeling of aristocracy and of jubilation every time I come across it.

There aren’t enough humanistic grotesques out there like Scala Sans, on Quadraat Sans. ABC Litera in Switzerland recently released a font, Jost Hochuli made it; I think it’s called ABC Allegra. It has a slight inclination to it, and is really a sort of antiqua-like grotesque. It’s great that this has come out.

On fashion in fonts

I’ve been following the font scene since 1997-1998, when I began to engage in professional design. And the first Adobe Originals, fairly simple by modern standards, once seemed the pinnacle of cool. Utopia was the first font that I found insanely beautiful and dreamed of typesetting. Unfortunately, it never appeared in Cyrillic, and even the expanded Latin alphabet appeared only after a good few years. Then there was this fascination with the Czechs, first of all with František Štorm. He had Biblon, Serapion, and a good non-contrasting Walbaum. Then I was drawn to the Dutch. These stunning fonts by Bram de Does: Lexicon, Trinite. Plus a new generation of designers, Lucas de Groot himself, who everyone flipped over. And later on, Underware. Then the Americans – Gotham came out… and a few years later, Knockout, then the stunning squared Archer font script with its rounded droplets. It was fantastic and very fresh back then. Now the Swiss have returned. It seems that the wheel of font fashion has turned full circle. And modernism is peeping through the window again, albeit with frills.

Archer by the Hoefler & Co. studio

Archer by the Hoefler & Co. studio

Archer by the Hoefler & Co. studio

Archer by the Hoefler & Co. studio

Archer by the Hoefler & Co. studio

Archer by the Hoefler & Co. studio

I already mentioned Štorm. He has a couple of fonts, which I would very much like to typeset, and I assure you that if I use it for something in contemporary Latvia, it will look brand new. I don’t know if it’ll come up to your standards for “todayness”, but in a context where designers and readers did not previously know it existed, it will look fresh, I can assure you. It seems like you forget you’re living in a visual space with the tastes that you yourself have influenced. But outside of Moscow, Saint Petersburg and a couple of other cities there is a vast Russia that has never seen Štorm, as in Latvia. Likewise in Belarus and the Ukraine, to a large extent. We constantly go round in a single relatively small circle of professionals, art directors, book designers and digital designers who we know. One and a half thousand people, in other words, and beyond this number and these cities there’s a completely different environment and way of life.

On purchasing fonts in an ideal world

I want to buy a font by its styles. The situation with Hoefler & Co. doesn’t suit me at all. Of course, you need to provide the option to buy just one style. In an ideal world, a small discount should be made even when buying italic along with the roman. Commercial Type](https://commercialtype.com/) does just that. In some cases, this provides for a psychological opportunity to buy one more design, which maybe I don’t need right now, but will use in the future, thereby making me spend a little more money. And Djurek at the Typonine store, it seems, did the same thing; his italics were sold at a discount, if you took the roman.

Before buying, I want to see the entire character set of the font exactly as it is represented in the font. I’ve come across the “problem of the single unsuccessful glyph” on occasion; these are the fonts that cannot be used due to just one or two unfortunate letters. It sometimes happens that I find out about this too late. We often come across the fact that there are some type foundries that don’t have any PDF specimens at all. And sometimes they do, but they’re no use. Or they suggest you use an online tester on the website in which the Cyrillic script doesn’t work. In PDF-format, there should be a full character set for at least one style, not just a few typeset phrases in Latin and Cyrillic, where you can’t even see all the numbers. I need a glyph-sheet, with absolutely all the glyphs.

A page from the PDF typeface sample of the Kazimir Text font from the type.today collection

A page from the PDF typeface sample of the Kazimir Text font from the type.today collection

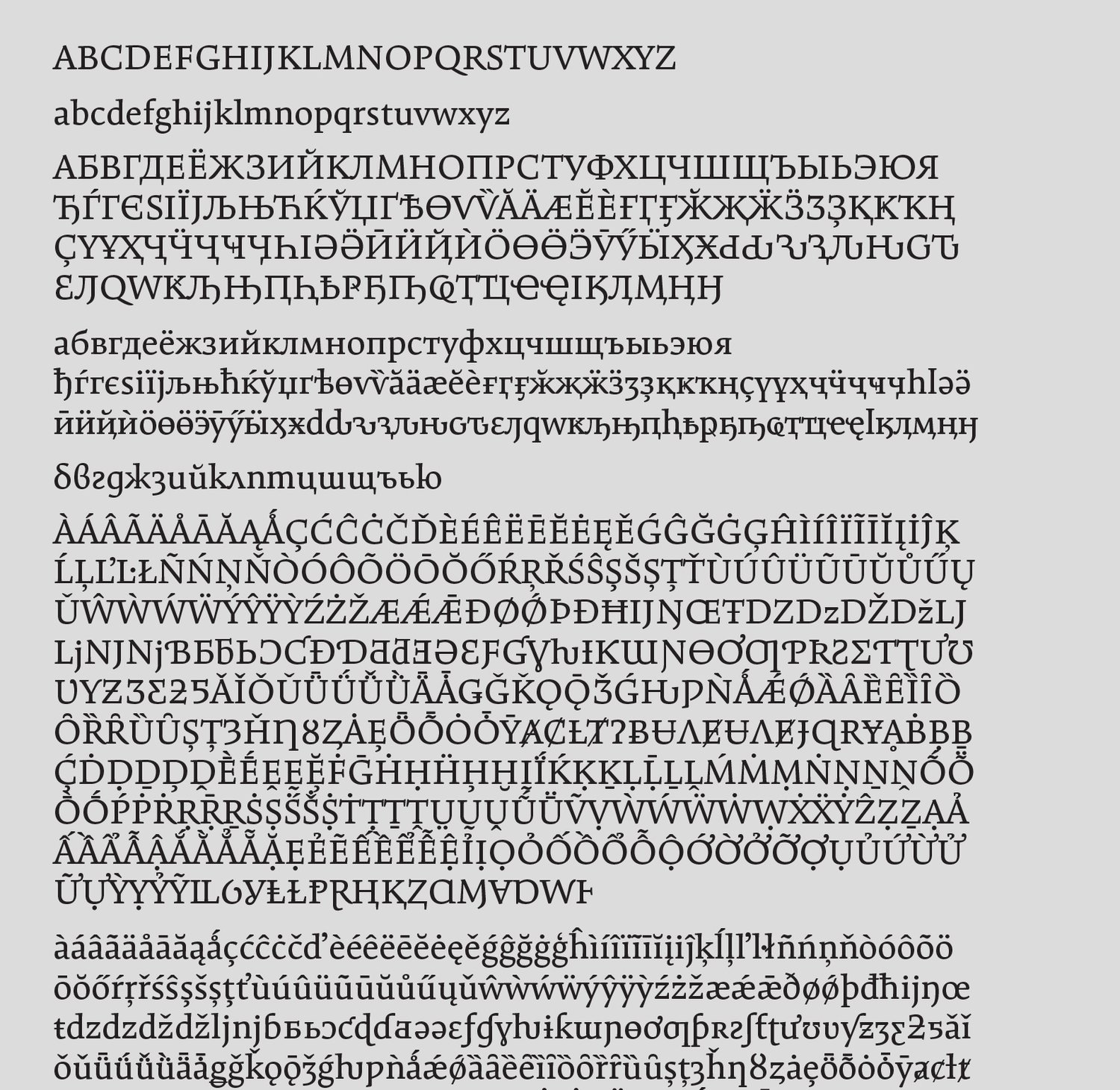

The ability to look at the entire content of a font is very important for me for two reasons. Firstly, as a typographer with experience, I don’t need descriptions of the OpenType-features: I can see everything in a codepage. I’ll skip it, and you can immediately see what’s there: whether there are alternatives, minuscule numbers, index numbers, and so on. My inspection takes 30 seconds. Of course, there may be flaws in the kerning and other technical things, but you can’t catch them except in the act of typesetting. Secondly, the most “problematic” letters are immediately visible: Cyrillic Б, Д, Ж, Й, Л, К, Ф, Ц, Ч, and Я. I skim through them, and if I’m immediately horrified, I look no further.

Of course, it now seems to me very strange to rasterize the specimens. By the way, Enschede still only lets you download the specimens, rasterized at 600 points. If you want more, you have to e-mail an order for a printout with a resolution of 1200, to be sent by post.

I would like to be able to buy or request printed specimens, well-printed, and well thought out. And there are very few examples of this. Perhaps Bilak, again. He regularly sends new items to his colleagues. I see a range of sizes in these, and this helps me even more than the test font in FontStand. I was really able to see Brioni there. I recently had a situation where it wasn’t possible to typeset a text sample of Brioni Text, because I was working on a PC and couldn’t use FontStand. Sometimes I turn round to friends on a Mac, who can give me examples of the set, but this isn’t always possible. And then there was a paper specimen from Typotheque. We looked at it with the editors, appreciated the daintiness of it (how the stroke is maintained thanks to the solid serifs), and this predetermined the selection. In my world, printed specimens still matter. I am ready to pay for them, but if it’s free, that’s great.

An understandable license is important. So that I know exactly what I can’t do with the font and what exactly I can. Sometimes there’s nothing written directly in the license about whether it’s possible to use the font in a logo and you’ll only find the answer after reading on that the restrictions of this license also apply when the font is transformed into curves. House Industries has a rather curious and very American license. There, for example, they have a clause stating that a font can be used for a company logo if its planned income is less than $ 5 million, and can’t be if it earns more. Can the designer who chooses a font foresee this? Of course, I understand why Americans do this: they’re more conservative in matters of licensing and are slightly freer in questions of price. But it’s terribly inconvenient. When working on a project, you have to think about the possible limitations all the time. That’s why in some cases I draw my own letters, which in density and rhythm somewhat resemble, something that could have been taken readymade. Partly due to this, I began to actively engage in lettering recently.

FontStand font testing service

FontStand font testing service

In an ideal world, I would like to be able to test the font before buying, even if only with a limited character set. Because this allows you to understand right away how it behaves and what you can do with it. The type foundries offering this opportunity today are few and far between. Moreover, I’m prepared to register when downloading. You can ask me for passport details at least – I’m ready to provide them. For a type designer, for the seller, this will be a guarantee, but for me it’s a great responsibility. And, if this font appears somewhere in my work, it means that I am a dishonest person and claims can be made against me. But I’m ready to go for it, because without testing fonts it’s very difficult to predict their behaviour on paper. It’s much easier on the web, but almost impossible with books.

The next thing that is very helpful is the opportunity in the store to make a selection of fonts with a specific alphabet, Cyrillic in particular. In general, a wide range of parameters for font selection is very useful. Especially if there are a lot of styles and especially if it’s a font department store. They increasingly interfere with animation; there are superfluous examples or freakish interface elements that you have to overcome before you get to the buy button or to a PDF link. For some reason, some font users forget that their site can be primarily a store. And the big companies forget this too. After an update a couple of years ago, the FontShop site became extremely inconvenient.

Perhaps, this is the most important thing, everything else is secondary. Things associated with ease of payment, working with a shopping basket, filling out registration forms, these are self-evident things. The fact that I have to face this is most likely a strange misunderstanding. In online stores selling clothing and books, this almost never happens. But here I have to put up with it. And all because we spend a long time choosing the fonts that we license, trying them out, and we become very attached to them before buying. We believe in them, so we are prepared to put in our best efforts in acquiring them. But I’ve already spoken about this. And ordinary buyers can simply refuse to purchase at all because of the inconvenience: “God, why all these tortures? You have to look for something, click all these additional things… there’s no PayPal option… Don’t you even want the font bought? Well, alright then, I’m not buying it.”

… and on purchases from type.today

On the whole, I find fault with nothing but choice. Yes, the range on offer seems a little limited. Naturally, the fonts are of a high quality and are carefully selected, but most of them are very distinct, special fonts. I rarely work with magazines, so half of the assortment is ruled out straight away. But I’m already looking for an opportunity to use some of them in some capacity. Amalta, for example. I noticed it a long while back and I really want to find a suitable project for it. I’m very glad that you’ve paid attention to the shortcomings of font stores and made yours head and shoulders above the rest. Now you just have to fill it out, and it will be wonderful.